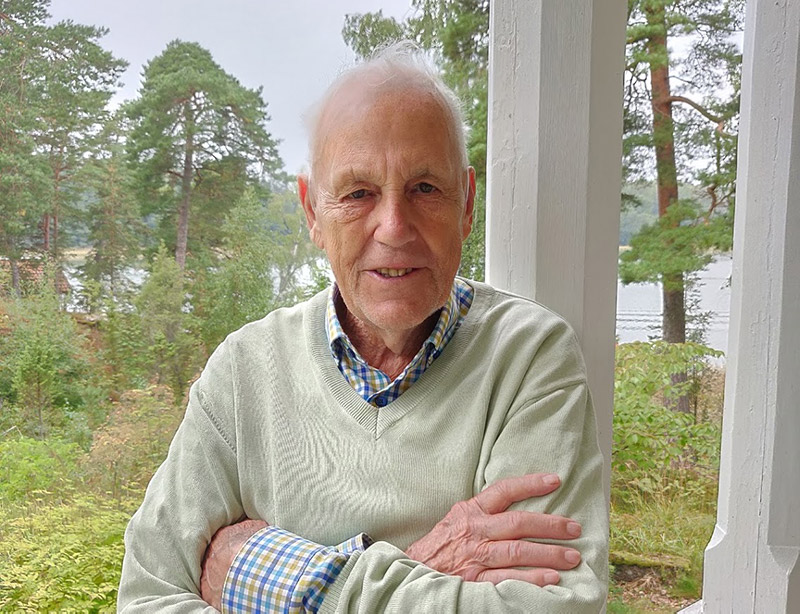

Erna Hennicot-Schoepges is a Luxembourgian politician, born 1941 in Dudelange. Growing up in Luxembourg after the Second World War she already experienced the benefits of the European idea in her childhood. Hennicot-Schoepges went to a catholic school in her hometown, but for her piano lessons she commuted to Brussels once a week. Also she naturally learned German, English and French as the Luxembourgian society is based on multilingualism. Nevertheless, Hennicot-Schoepges’ early career was shaped by a lot of limitations. For following her dream of becoming a professional pianist she was lacking the financial means. And when she got married she prematurely had to quit her job as a radio host. Eventually these experiences motivated her to take an active role and become a politician. Hennicot-Schoepges began as the mayor of Walferdange in 1987 and was among others Minister of Culture in Luxembourg from 1995 until 2004 as well as Member of the European Parliament from 2004 until 2009.

In her conversation with Samuel Hamen, she talks about managing family and career at times when there was no daycare, how her work has changed with the enlargement of the European Union in 2004 as well as the meaning and challenge of cultural politics then and now.

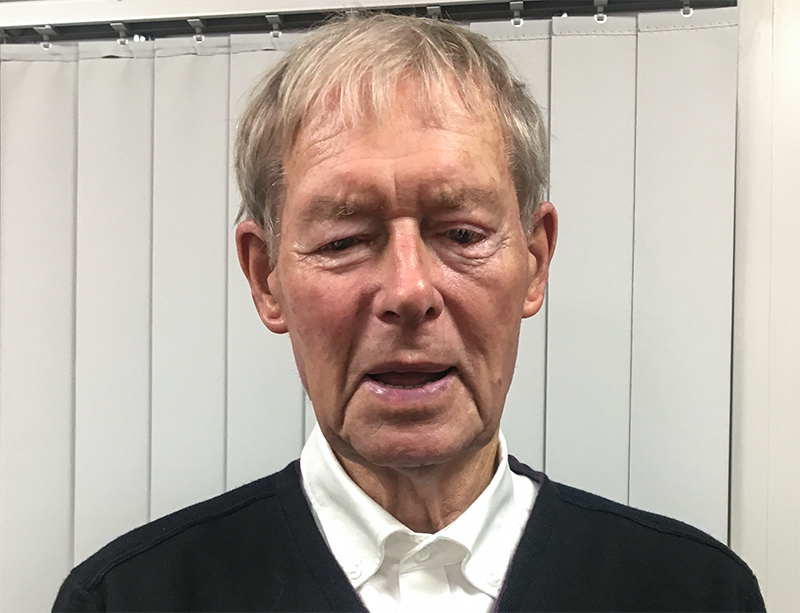

Erna Hennicot-Schoepges was interviewed by the cultural journalist, literary critic and author Samuel Hamen.

Interview Highlights

On childhood and crossing borders

My parents, siblings and I went to visit our relatives in Germany immediately after the war. My brother bought his first car in 1949, so we drove to the Eifel to visit my father’s relatives. That was my first visit abroad. And because of my piano studies at age 15, I actually started travelling to Brussels every week to go to the conservatory. For this reason, foreign countries became a topic that was no longer foreign to me. But it was a journey that only took me there to study. And I did not find it extraordinary in any way, because that was my weekly routine and I also had friends there and I also learned to manage on my own there. On the train I naturally met many strangers.

On work

That is exactly what might have been one of the motivations for me personally to get into politics, when I was asked to participate in a party and to run for office. It was to play an active role in this field and to not only influence from the outside, but to really roll up my sleeves. I think, it is nevertheless important today to think back to the situation of those generations who have now all reached retirement age. There were limits for us. And those limits were measured by the financial situation of our parents. My friend from Rumelange, whose father was a bus driver, and I, we were the only two children at the Lycée who came from a working-class environment. All the other kids, their parents were lawyers, doctors, or business people. So that was also one of the limits that was always set for me. And to deal with that, that was of course also a challenge. But that never depressed me.

On politics and culture

For me, the main question we are facing today is first of all a big transformation of what we understand as democracy. We used to understand politics as a form of service. Today one is under the impression that career politics has gained the upper hand, that one becomes a politician in order to organise everything in a way that leads to their election. And if you have been elected, you want to stay elected. And that is fundamentally a weakness of devoting oneself to politics, which is noticeable at the local and national level, as it has a rather detrimental effect on the credibility of politician.

That is one thing. But another is that we did not talk enough about culture when we founded the European Union. We forgot that Robert Schuman had said in his speech on 9 May [the Schuman Declaration on 9 May 1950]: We want to ‘unir des citoyens et non coaliser des états’, which means that we should see Europe in a way in which the diversity that exists on a cultural level should also be part of our fundamental values as Europeans. That is why we cannot pass judgement on subjects such as the dominant culture [Leitkultur] because we know it reflects only a small portion of those, who belong to Europe, of those who identify with the European idea. We cannot force everyone else to give up their culture in order to be a part of Europe either.

On values and future

Well, by nature I was sometimes melancholic or depressed, but that had nothing to do with my vision of the future. I think that what has guided me personally was a kind of basic faith in God. And that is how, through my education, my father’s statement – who knows what it is good for – affected how I viewed all the things that happened. For now, it is what it is – who knows what will come of it? But what kept me going were the fundamental values of honesty, of treating others with dignity – basically what my religious education had provided me with. For this reason, I did not see the future in a pessimistic nor in an optimistic way, because life was not easy in my time. You didn’t have a lot of money, and that made it so that you couldn’t buy all of the books that you wanted to have, and that you were also limited in terms of travel. You simply had to earn everything, though that was not a reason to avoid looking into the future. You felt that you could at least work your way up. You could move beyond that, if you worked a lot and just considered what was possible.

On freedom

The notion of freedom is not supposed to mean that I can do anything I want. Freedom always has its limits, which is where it offends the other. However, viewed with respect to communication, interpersonal relations and our society as it exists today with the current media, then we have to say: This freedom, it does not mean that you get to do absolutely everything that you are able to do. There also have to be rules which are accepted by everyone. And if we then analyse freedom in relation to truth and honesty, then we do find out where those limits lie.