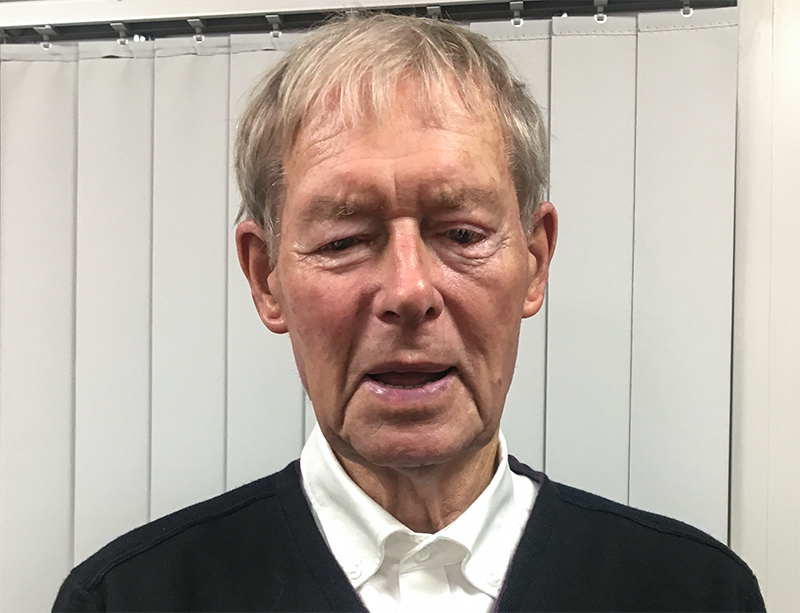

Mícheál Ó Muircheartaigh is an Irish sports commentator and journalist. He became one of the most famous television reporters in Ireland and is also known as the “Voice of the Gaelic Games”.

He was born 1930 in Dún Síon near Dingle, where he grew up on a farm with nine siblings. From 1945 to 1948 he completed his studies in Dublin to become a teacher. His professional broadcasting career started in 1949, when he gave a test commentary at a hurling game. After that he worked as a part-time reporter for the Irish public broadcaster Raidió Teilifís Éireann and continued teaching until the 1980s, when his full-time sports commentator career started. For six decades he commented on countless sports events in Ireland, which has earned him a place in The Guiness Book of Records. In 1999 he received an honorary doctorate for his engagement in broadcasting by the National University of Ireland, Galway.

In his conversation with Bairbre Meade he talks about the invention and his fascination for Gaelic games, why he is glad he grew up speaking both English and Irish as well as the idea of togetherness in Irish poetry. Furthermore, he remembers the special moments receiving letters from relatives that emigrated to the US in his youth and why he supports that three of his eight children are living abroad today.

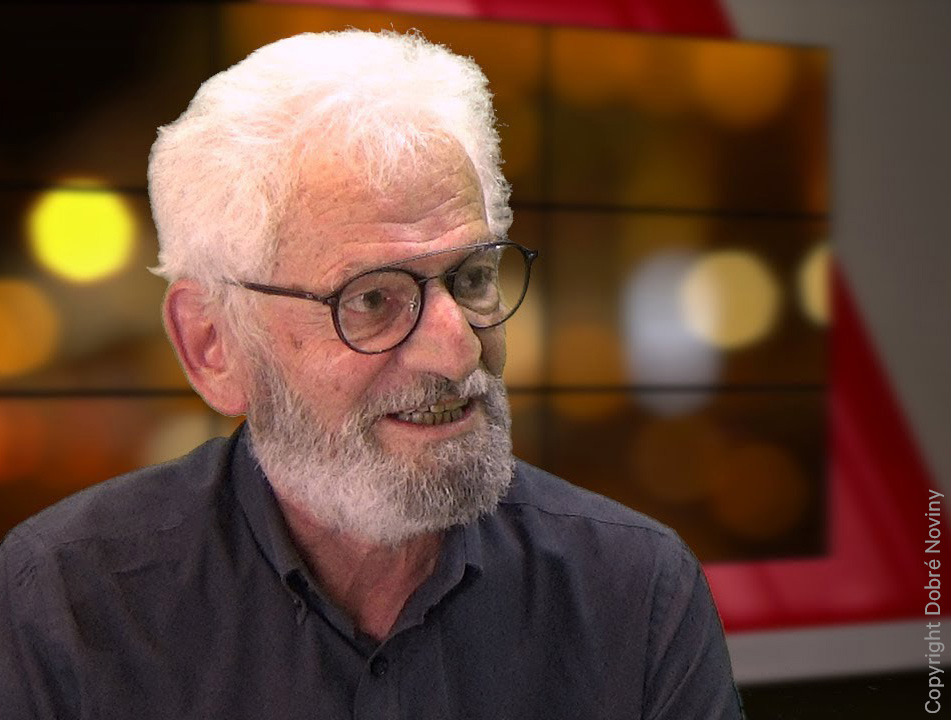

Mícheál Ó Muircheartaigh was interviewed by Bairbre Meade, a writer from Tipperary.

Interview Highlights

On childhood

I’m from the parish of Dingle in County Kerry. Looking out, one of our fields is within fifty yards of the Atlantic Ocean, which stretches all the way across to the United States. We used to go down there when the tide was out, people that had to travel to Cork at that time, selling butter and fish, and they went on horseback. I’m talking about the 1800s, there were wars going on in lots of places and there was a great demand for these products, people went on saddleback all the way down a hundred miles to Cork, bringing their fish, or whatever provisions they wanted to sell, with them, selling them, coming home with maybe not all the money but with a fair share of it. And to this day that road that started maybe fifty yards from our field ’tis known as the Cork Road and that goes back well over two hundred years ago at the beginning. So, I was born in that place, my father was a farmer, ’twouldn’t be a big farmer, we’d what people would say the grass of maybe ten or twelve cows.

And land — fifty-three acres that you say in the annual census of arable land. But ’twas a most enjoyable place to be there. From a very early age, we were out in the fields. Whatever work was being done, the whole family — there was five boys and three girls — all the lads would be out helping, and that was wonderful. Even before you went to school, you brought in the cows, you brought in the horse to bring the milk to the creamery. You did something. And then you went off and you walked the three miles into Dingle to the school, crossed fields to make it shorter at times but I thought it was great, y’know? I learned something at a very young age, and it came from my grandmother at that time, and she said, a prayer taught to me in my youth, “To wake every morning with enthusiasm for the day ahead,” that was the end of the prayer. “To wake every morning with enthusiasm for the day ahead.” And I think it’s a great motto. I always stuck to that. Be full of hope in the morning, be full of hope in the beginning of the year, and spread that, if you like, among people, in schools and wherever you got yourself in years to come.

On language

I grew up speaking both languages. Mostly Irish. Where I was at the time was called a breacGaeltacht. ’Twas neither in the Gaeltacht, nor ’twas out of it. The people were beginning to speak the two languages, and I advocate y’know having two languages. They help each other. But I grew up with, we spoke whatever was spoken to us. And I think we were good at both of them because there was a split, y’know. Anyone who speaks to you in English, answer them in English; anyone that speaks to you in Irish, answer them in that language. So there was no trouble and there were no problems about things like that.

On the beginning of his career

There was a little notice appeared somewhere that Raidió Éireann — as it was at the time; the television hadn’t come in — they were holding rehearsals in Croke Park for people interested in becoming a sports commentator. And the attraction was free admittance at games such as Sunday, ’twasn’t the big game but there were two games one after the other going on, and a big crowd turned up, y’know, from the University College Dublin and from Drumcondra and from different places, and we all got five minutes. And I got fifteen. And I was asked there and then if I would broadcast the Railway Cup Final on St Patrick’s Day which was around the corner. And being an innocent Kerry man, I said, why not?

On the European Idea

I always thought that we were European. In the ’60s now there was a movement, the European Teachers Group. [It] used to meet a lot, discussing things that somebody would know: about Europe’s system, to know how some of those would merge into some of ours and vice versa. I think it was at a certain stage, there was great move to think European.

And I always thought that, and a lot of the people I knew did. That we’re too small. And I think that trend I remember now, ’twould be the minute the war was over. Winston Churchill, who was never friendly towards Ireland, really, he made a statement: “Only a United States of Europe will put an end to wars in Europe.”

On cultural exchange between Ireland and Europe

If a story, a poem carries a moral, it does not need to be directly stated in the text. If you feel a human blessing in the text—that is the correct interpretation of literature. Never has a novel or a poem called for a war, and hopefully they never will. […] I have never intended for my books to give concrete advice. That was not my idea. I recommend that people try to be peaceful. It would be really good for this world if people tried to imagine it in peace, and not in war.

On freedom

Freedom, I think, the principal thing about freedom, it should administer the government of the time should administer justice. And freedom means to me that you’re allowed think in a different way. Do things in a different way. Develop things in a different way. And that nobody would object to that, [tell you] you have no right to do that. That people have rights to do things the way they do. They might not seem as good to other people, but freedom would mean closing your eyes to a lot of things, and again going back to what I said, “Ná taibhair na breithe ar gcead scéal go mbeirigh an taobh eile d’ort.” Don’t give judgement until you hear two sides of a story. And freedom means giving the people freedom to do that, rather than making them do that. That’s the way to go. This is the way the majority thinks. Freedom would be fair to people who have different views. Provided they’re not breaking laws that are considered good laws.