Niels Barfoed is a Danish writer and literary critic, born 1931 in Copenhagen, where he grew up during the war. He initially learned about Europe through literature – first thanks to his father’s old illustrated books, later through modern literature, e.g. from Villy Sørensen. Barfoed studied history of literature in Copenhagen and at Princeton University and received his doctorate in 1978. For a long time, he was much more interested in art than in politics, which changed tremendously in the 1960s. During several travels to Eastern Europe he made friends with intellectuals and creatives and became an important advocate for persecuted writers and dissidents. He used his position as a critic, journalist, newspaper and journal editor to smuggle Western literature to the East and bring manuscripts of Eastern writers to the West. Later Barfoed also contributed to the Danish literary scene as a lecturer and researcher, and as president of Danish PEN.

In his conversation with Markus Floris Christensen he talks about Danishness, which in his view is characterized by the loyalty to the crown, the feeling of security and a trust that everything will work out. Furthermore, Barfoed shares some of his most rememberable stories from his travels to Eastern Europe in the 1970s and 1980s, including meetings with Herta Müller and Wolf Biermann. Finally, he encourages today’s young generation to experience other cultures by travelling, and not just digitally or gastronomically.

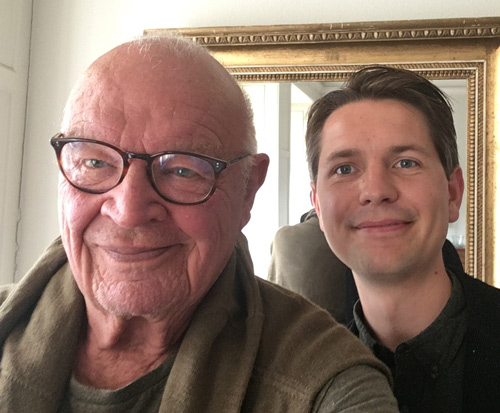

Niels Barfoed was interviewed by Markus Floris Christensen, who is a PhD student in Literature at Europa-Universität Flensburg.

Interview Highlights

On childhood

I am a child of war. I was 9 when the Germans came and 14 when they left. Then we knew that there was something called Europe, but only as it existed in my father’s old illustrated books, in which you could see Florence, which at that time was a place that found itself in great chaos, and which was a smouldering ruin all throughout the war.

And that extreme isolation, was broken in ’45. But, of course, it wasn’t replaced by an actual opening, a dynamic opening towards greater Europe, because all around us there were only ruins. And there was no denying it, really. And if you tried to anyway, you had to be older and more daring, or you had to move past it and on to something which looked like a Europe – if that’s what you wanted.

Europe to us was something unknown, and that is often difficult for young people to understand. Europe did not exist in my childhood. Only figuratively speaking in writing and in badly-printed photographs and badly-printed books.

On conflict & resistance

Well, in my family you followed the mainstream, in other words, tendencies or general ideas held by the public, which was to surrender completely, to close your eyes and expect it all to pass. That was my father’s attitude. I won’t hold him accountable for it today. Our house was actually on the corner of Ny Kongensgade and Vester Voldgade, with a clear vision of the Great Synagogue, and there was also a Jewish building there, with private homes and meeting rooms.

And then they came in October 1943 and it is thought-provoking to see yourself standing with your father and looking down and watching that street, knowing that we see it, but don’t really see it, you know? That was our general attitude.

And well, yes, there were guards, and there were people who were nationally and ethically as well as morally and politically aware. My father was not one of those people. He was a dreamer and had a sort of artistic nature. He didn’t really need anything other than his drawings, pencils, some cigarettes and his leather armchair. That was all he required to feel comfortable. […]

But that was the general backdrop. We listened to English BBC broadcasts with the help of a jamming station – wau, wau, wau [sounds imitating the radio]. We pretended the Germans weren’t there. When they entered a tram, we would move to the opposite end of it, because the presence of a German soldier could easily create some chaos. That’s how it was.

On European challenges

What we didn’t know was that one day in 2019 you would realise how little liberalism actually had taken root. So little. In Eastern Europe, liberalism is almost as present as corruption, and it evolves into corruption under the circumstances in Eastern European today.

You wanted liberalism to be established on its own terms, and it did for a long period of time. That’s exactly what’s at stake today, isn’t it? Those roots have turned out to not be deep enough. In Hungary, in Austria, in Poland. Austria is part of this now. You find a strange sort of melancholy connected to the exact thing we were fighting for, and which we were successful with, thanks to Gorbachev, thanks to many factors. It was instituted where it rightly belonged – because now, what belongs together, grows together and as Willy Brandt said by Brandenburg Gate – that is exactly what’s at stake right now. […]

Integration based on the EU’s conditions. That’s what’s at stake now.

On the future of the EU

In the beginning, I wasn’t a very big supporter of the common market, but that changed since then. Because it actually functions as a peace project too. It ties together that which should never be untied.

I’ve seen the fall of the Nazi regime, and I’ve seen France and Germany beat the hell out of each other. And if the axis that has been created can be kept as axis for peace, by which Kohl and Mitterrand stood hand-in-hand by the graves of soldiers – well, what more could you want? If one wants to be protected, that is.

But that’s not where we’re at. Not just yet. And the EU as a peace project, though young people won’t buy that today. It’s not enough. We could bring all the wars and occupations to the table that we wanted, but the young people cannot imagine what would make France and Germany fight. That’s a project which no longer sounds convincing. And if you remove that project from the EU I know, then you’re left with so much administration, and so little of the other stuff.