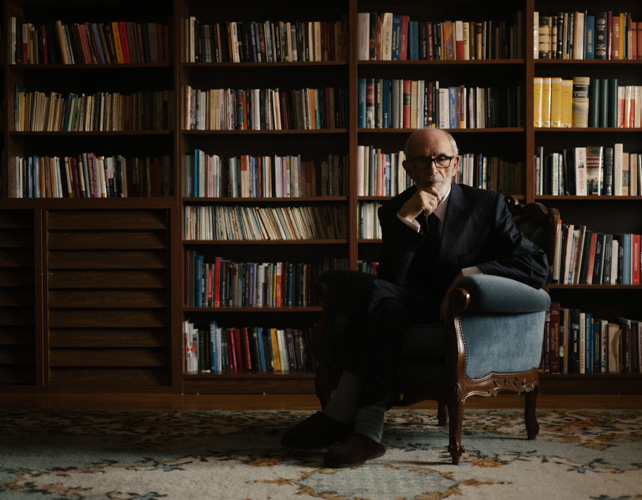

The Albanian author, literary scholar and critic, and political commentator Rexhep Qosja was born 1936 in Vuthaj [Vusanje] in Montenegro. He studied Albanian studies and literature in Pristina and Belgrade, and later became the head of the Institute for Albanian Studies in Pristina. As a literary historian, Qosja’s focus has been on the Albanian Renaissance, and as a political activist, on the issue of Kosovo, the most significant component of the ‘Albanian question’. Qosja was part of the Kosovar delegation to the, ultimately unsuccessful, peace talks with Slobodan Milošević in Rambouillet, France, in 1998. Following the end of the Kosovo war, he was also a member of the interim government of Kosovo supported by the UN. Amongst his most famous work is the novel “Death Comes from Such Eyes” (1974). Qosja lives in in Prishtina.

In his conversation with Nora Sefa he talks about how Albanians’ views of Europe have shifted over time, and why he believes in a Europe which is pluralist in cultural, faith, and ethnic identities.

Rexhep Qosja was interviewed by Nora Sefa, who was born in Pristina in 1992 and has lived in Germany since 1998. Sefa is currently studying towards a master’s degree in peace and conflict studies and also works as a journalist.

Interview Highlights

Studying in Belgrade

Not many Albanian students studied in Belgrade [when I studied there]. Few, very few Albanians studied medicine, engineering, sciences, other professions. That attitude, full of discrimination, injustice, and violence against Albanians, which would develop later, later, especially after the seventies, was not openly displayed then. At that time, before the seventies, that discrimination was not so apparent, there was a tolerance displayed toward Albanians, a tolerance that was sort of formal. The number of Albanians in Belgrade was significant then: some did manual labour and some studied. Look, it cannot be said that, at that time, the position toward Albanian students was openly negative, but […] there was nevertheless a hidden attitude that was contemptuous toward us Albanians.

About freedom

In one respect, we [Kosovars] are already free: we have been liberated from occupation by Serbia. And by Yugoslavia. From 1912 onwards, Kosovo was occupied by Serbia. We have been liberated from that occupation, but—! Freedom is a word full of meaning, it is an idea full of content, with many desires, much effort, a lot of realised and unrealised rights. [….] The French writer, André Gide […] wrote a very significant sentence that I used to end a book of my own. He says, “To know how to free oneself is nothing; the arduous thing is to know what to do with one’s freedom.” We won our freedom through war, the war of the Kosovo Liberation Army, and through the intervention of NATO, in fact of the US, and they deserve great credit, they were pivotal to the liberation of Kosovo, but in my opinion, we are not using that freedom which we gained properly, no. Today, the political class of Kosovo has not passed the democratic test of how Kosovo should be if its existence is to be in the interest of all the people.

About religion

Also, they [the EU] did not agree to start membership negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia! This was not a good decision on Europe’s part. Someone has come up with the geographical notion of the Western Balkans. I don’t know what this geographical notion means! The Western Balkans!

[First,] it was just the Balkans. Now there’s the Western Balkans too! It includes Albania, Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Bosnia. And Serbia too. All these states have inhabitants of the Muslim faith. There are many in Albania, many more in Macedonia, and in Kosovo they are 95 percent of the population. Montenegro also has a Muslim population, and Bosnia too has a large number of Muslims. Perhaps Europe, or someone in Europe, came up with this term of the Western Balkans because there are so many inhabitants of the Islamic faith in these countries? It is not good to think like this. And it is not good to think this way in a united Europe. [….] Croatia and Slovenia are completely Christian, with some refugees here and there who are Muslim. Look, it’s not good. Albanians are a people with three religions: Catholic, Orthodox, and Muslim. And Albanians are a people with unusual religious tolerance. Albanians have not experienced the religious conflict that Europe once did. Europe is familiar with the concept of a Thirty Years‘ War for religion, or perhaps longer than thirty years. There are certainly people in Europe who view us with prejudice, but I hope that the number of those who do not have these prejudices is greater.

On cultural awareness

I think that the Albanians, as a people of three faiths, and given their particular geographic location, are predestined by this geography and by their three faiths not to divide and fracture West and East, but to build bridges between West and East. In the Balkans, the East and the West have confronted one another for centuries, they have fought for domination, to exploit the Balkans, to use the Balkans. But in the Balkans, at the same time, Western and Eastern cultures have met, intertwined, influenced each other, and fallen in love. Cultures and civilisations do not fight each other. Civilisations and cultures meet, learn from each other. They are enriched, and they grow, when they meet.

I think that popular Albanian music, or Melos, is one of the richest forms of music in Europe and the most beautiful. Popular Melos, folk songs, Albanian folk dances—a great and beautiful treasure. Why? How? Because they express the skill of the Albanians, but also reflect historical influences, from the Greeks, Italians, Turks, and Arabs. So lovely. Albanian culture has been enriched and Albanian civilisation has been enriched. Thus, Albanians are geographically, religiously, culturally, and historically destined, not to divide, but to bring the West and the East closer together, to build bridges between them, bridges of peace, bridges of understanding, bridges of cooperation, bridges of coexistence. The best bridge for a better present and future of the West and the East!

On the future

There are pessimists, pessimists who write desperately about the future of Europe. Me? I believe in the future of Europe; I believe and I want to believe. Europe has always had wise people, clever people, who have done a lot, not only for Europe, but also for humanity. Those people will not let Europe decline. I think that Europe will be rebuilt, developed, enriched, institutionalised—better than it is today. We see that in Europe there are corrupt people, there is a corrupt bureaucracy today in Europe. I hope that Europe will be liberated from them and will become a cleaner Europe in the political, democratic, social, moral, and ethical sense, so I believe in the future of a better Europe. The world needs a united Europe. […]Here is one piece of advice [for the younger generation in Europe]. Montesquieu, one of the founders of the philosophy of democracy, has an opinion that I would like to be remembered, and repeated often. He said that the tyranny of the prince—of the prince, of the ruler—is less harmful to the general interest than the apathy of the people. I want you, the younger generation, not to be apathetic. To be active, to be hard workers, to have demands, because only in this manner, with your active, hardworking behaviour, with your demands, your ideas, your desires, your rights, will you drive Europe forward, as we wish.