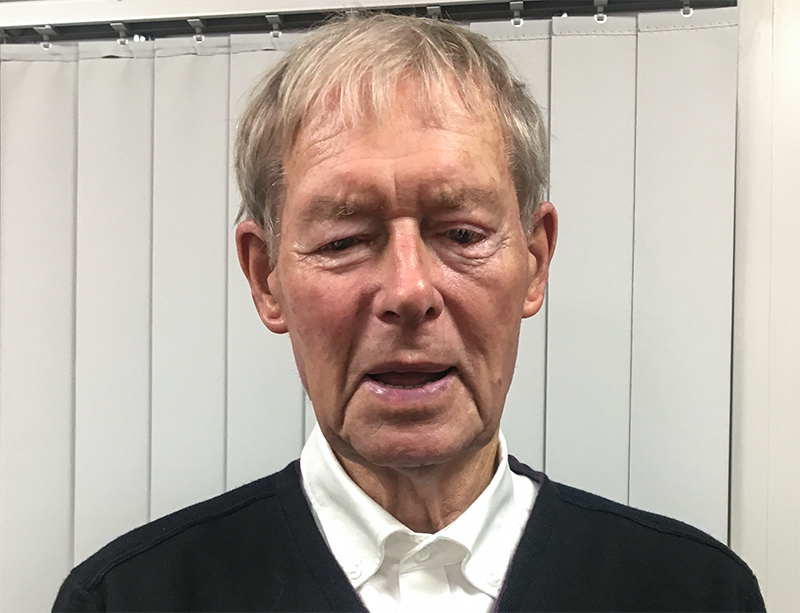

Vera Szekeres Varsa, born in 1933 in Budapest, is a Hungarian language educator and former chair of the Hungarian branch of Amnesty International.

Szekeres Varsa first wanted to become a literary translator, but became a language educator instead, teaching Russian, English, and French. Having survived the holocaust as a child, as a teacher she says she always sought to demonstrate the value of freedom and independence to others when having none herself as a child.

Her options initially seemed limited due to her family background, she nevertheless succeeded in leading the fearless life she wanted to. After the fall of Communism in Hungary, she joined the liberal SZDSZ party and served as a member of the District Council in Budapest. She later served as president of Amnesty International in Hungary for many years. Vera Szekeres Varsa has a daughter, three grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren.

In this conversation, Vera Szekeres Varsa speaks about her childhood, her studies and passion for teaching. She also discusses her joy of being European, which for instance finds expression in the selection of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” as her ringtone. Szekeres Varsa says she feels both Hungarian and European, but as a holocaust survivor, she admits that the trauma she experienced as a Jewish child had a similarly strong impact on her identity and values.

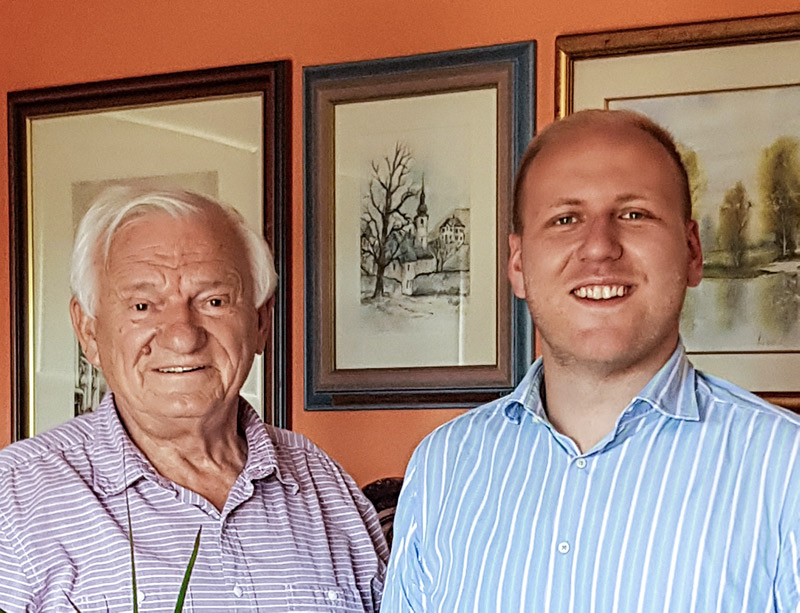

Vera Szekeres Varsa was interviewed by Gabriella Dohi, who is a photo, radio and video journalist, and also leads tours of the Jewish district of Budapest. She is currently enrolled in the doctoral program for Film Media and Contemporary Culture at the Práter Street Vocational School and journalism at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE).

Interview Highlights

On the meaning of “Shoah”

“[…] the war came, the siege and the Holocaust. I’d rather use the word “Shoah” instead, let me say that. Because this is a Hebrew word. “Holocaust” is a more recent expression, as we know. In my interpretation it is a ‘burning sacrifice’. Nazism did not intend to denote a sacrifice to their gods or whatever they believed in. They were pagans, after all. […] I do not want to accept that there was anything respectable or good about it or that there was any good cause behind it. No. Nazism is purely evil.”

On growing up as a child in a Jewish family in Hungary

My mother put my yellow star in her purse with the yellow silk yarn […]. [She] wanted to make sure we had some. She was planning to sew the yellow star back on my coat before going home, which had to be done with yellow yarn. The question was either: Why would a Jewish couple walk in the street with a child who is not Jewish. Or: If the child was also a Jew, why would an eleven-year old not wear her star? This was very dangerous. So my mother put it in her purse, but when my father noticed it, he snatched it from the purse with a very determined motion and quickly stuffed it in his own pocket. Because it was dangerous to carry a spare yellow star, and when it came to danger, it was the man who was expected to face it. […] I didn’t play with dolls much anymore by then, but I had [my] Györgyi-doll with me because mother advised me to always have it on me, so people could see that I was a small child. That’s why my Györgyi doll would always come with me on the walks.

On her professional success

I was the youngest head teacher ever appointed in the country. I was twenty-eight years old. Later, when I got to know my colleagues, they admitted that initially they had thought that I was some apparatchik for whom they wanted to find a position. But I wasn’t one, of course; I wasn’t a party member!

On values

My values were cultural, the bourgeois attitude. Trustworthiness was a sacred thing, too. One would never tell lies because it meant humiliating oneself. You must speak your mind and be responsible for your opinion. […] Culture was a great value. […] And that this was our homeland, we had to live here. And it was a homeland for all the others, too. If somebody had a different opinion about something, we respected it if that person was serious about it. And if one was of this religion or that, and had this view or another, and the person complied with that and had humane opinions, not such horrible things, but serious opinions—we respected them.

On the meaning of freedom and human dignity

I taught people about the love of freedom and about how to form their own opinion. There are many who can vouch for this, and in fact they do. It was my birthday recently and I didn’t just get simple birthday wishes. Former students who are over sixty now wrote to me saying that I taught them to think, to form an independent opinion, to respect others and to have a thirst for knowledge. I worked at Amnesty for six years. I worked for other people’s freedom and for human dignity. I’m very proud that at an international Amnesty congress I was the one who suggested that dignity should be included in the principles. Human dignity should also be among the basic principles we keep repeating. How far am I ready to go for it? I’ll stand up for it; for others’ dignity, too.

Political awareness

I cried when Stalin died. But when the crimes that happened under Stalin came to light, I couldn’t believe anymore in the glory of the Soviet Union. I had questions again, like, “How can it be that the history of the party was written by Stalin, and it says everywhere that the great Stalin realised this and that, and no one ever knew any better than Stalin?” My faith kept falling apart then.

On her attachment to Europe

If we were still up in the sky with the stork, I’d say Europe; nothing else could come into consideration. And now if we were above Europe, I’d suggest to find a hexagon-shaped country and move toward the sea. I’d say: “We don’t need to go as far as the ocean but just to find that bright spot well-lit by streetlights before reaching it. Now let’s descend and find the 5th or 6th or 7th arrondissement.” And then I’d kindly ask it to drop me there somewhere.