Interview by Tomas Wedin

Sweden, October 2019

„Concerns, confidences and fears are like a brushwood that you laboriously force your way into. You have nothing else in mind but the twigs hitting your face and prickly branches that grab your clothes. But when the forest opens to a peaceful glade, you suddenly feel a cold wind. Peace itself gives way to a throbbing worry; peacefulness has an offside which is emptiness, representations of paradise are not only boring – a formless terror lurking in the silent light.”

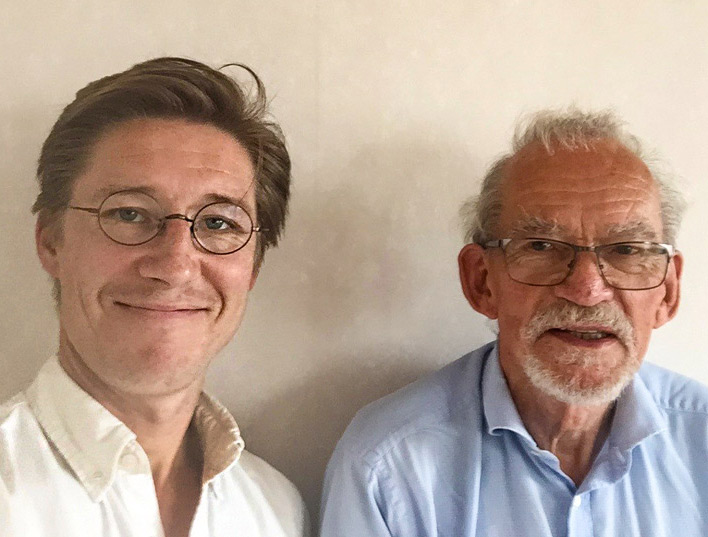

Wedin: In front of me sits Sven-Eric Liedman, Professor Emeritus in history of ideas, born in 1939, only a few months before the outbreak of the war. Within a few days, he will be turning 80. In the 1960s, Liedman switched from philosophy to the history of ideas and teaching. In 1966, he defended his thesis “The organic life of the German debate 1795-1845”, since then, he has continued to work in the field of history of ideas and among other titles, wrote “Friedrich Engels thoughts about the natural philosophy of the Swedish physician and researcher Israel Hwasser”. Through this path he advanced further into the history of ideas of specialization, about Anders Berch and Swedish economic thought in the 18th century. He has written about the transformation of the concept of form and matter from antiquity to the present, to name but a few examples of Liedman’s extensive contribution to the research on ideas and learning history in Sweden. In addition, he has made significant contributions to Swedish popular education with his works on the history of modernity and the concept of knowledge. He played an active role there and continues to participate actively in discussions on educational issues and the relevance of the concept of Bildung. He has written a comprehensive survey book on the history of political ideas, which has been published with varying regularity since 1972 and is currently revising its 15th edition. Since the mid-1960s, at the latest, he has also been working on Karl Marx thought, and in 2015 he published a biography of over 800 pages about Marx’s life and thought, which has been translated into several languages and attracted attention in many countries. Parallel to his work at both universities and his active contribution to the public debate on a variety of topics, he was a literary critic at Sydsvenska Dagbladet for no less than 30 years.

My name is Tomas Wedin. I was born in 1981 and am interviewing Sven-Eric Liedman. I completed my dissertation at the Department of Literature, History of Ideas and Religion at the University of Gothenburg (GU) in 2018. Before I started working on my dissertation, I worked as a high school teacher of History and Spanish for several years, among other things. I am currently working on an anthology of ideological critique with two colleagues and will be a guest researcher at École des Hautes études en sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris in 2019-2022, working on a project regardingthe reflection group of political theory led by the French historian François Furet in his time as the head of EHESS.

Wedin: Sven-Eric Liedman – should we start the interview?

Liedman: Yes.

Wedin: What do you associate with the different places – for example, Vittskövle, Degeberga – where you grew up? Are there certain sensations – like smells, noises, aromas, etc. – that you associate with different places?

Liedman: Yes, it is clear that these first environments and surroundings play a huge role. Ah… It’s still like I’m in love with the rural scents. So, if you live here in Gothenburg, amid the Masthugget district, as I do for the most part now, there are far fewer smells, noises, far fewer birds than I had in my hometown growing up. But at the same time, you’ll certainly feel at home. But it’s clear: The childhood environment probably plays a significant role, and for me, that was mainly Vittskövle. Even though the big vicarage in Vittskövle had a sad ending; it collapsed in 1950 when I was 11 ½ years old. And then somehow it felt like my childhood had ended. Yet so much of my life is in a way still connected to this first environment. Nonetheless, other settings, like Lund and Gothenburg, have played their parts for me since then.

Wedin: What did you talk about at your family’s dinner table?

Liedman: Well, my father was a priest, a pastor in the Swedish church, which at that time was a state church. One might say, he was a learned theologian. He came from an impoverished background but had collected much knowledge. His mother played a significant role for him, and she was book smart. So eventually he had a vast repertoire of knowledge. Admittedly, maybe he was slightly old-fashioned but still knowledgeable. I understand, of course, that it was an advantage for me. Very early in my childhood and youth there was such a large part of the Swedish vocabulary available to me, including many foreign words. I’ve always enjoyed that. My mother wasn’t a literary person. She was more practical, a housewife of sorts, very temperamental. However, of course, she played a huge role in my upbringing as well. I also have an older brother who was almost three years older than me, in development with all the means to it. But it was a small family and one that now seems very old-fashioned. For example, we had a maid in my first years until the end of the war. That now seems (laughs) very strange. But it was necessary for this huge house, which also gave my mother plenty of work, but that is ages ago now.

Wedin: It was big if I’m not mistaken, like 11, 12 rooms or was it even bigger?

Liedman: Yes, big indeed, there was even a large attic. It was fun to play there as a boy. But it was known to be scary, coming with stories of spooks and ghosts. My father’s predecessor believed in ghosts (laughs). But we never saw any, and I have always been immune against such things. The folklores in the region just were like that; “The old priest who goes around”, and stories of that sort.

Wedin: You mentioned your grandmother earlier.

Liedman: Yes.

Wedin: Would you like to tell us more about her significance for your father?

Liedman: My grandmother on my father’s side was a certified primary school teacher. She came from a small farmhouse outside Skövde and then went to the school seminar in Skara. She was very young when she came to be a teacher in Hallandsåsen, Båstad. And then had the luck, or the misfortune, to meet my grandfather.

Wedin: Where are we approximately, around the end of the 19th century?

Liedman: Yes, this is the end of the 19th century. And the two of them fell in love with each other. He was a baker and confectioner and pretty good at that, but a lousy businessman. He had a pastry shop and a bakery in Båstad. They got married. At that time, a primary school teacher who got married, that kind of teacher would have to stop work immediately. And that was her destiny. So, she gave birth to a total of nine children, eight of whom reached adulthood and she was, in a way, somewhat resentful about this, about her life’s fate. She was a person who didn’t think it was so much fun to give birth or – as no one feels giving birth is fun – to have children. But she was a mother who had, above all, bound herself partly to an older sister of my father and somewhat to my father because their heads worked in similar ways.

And anyway, the sister was still a girl, and at the time it meant that she had to go to work while my father […]. Well, a dedicated teacher said that he had to go on with his studies, and he was allowed to do so. And so, despite great financial sacrifices, with the help of my grandfather’s mother, they made it. My grandfather’s father had died very, very young due to tuberculosis. He was only a little over twenty years old. But my grandfather’s mother lived in Malmö, and it really were her and her new husband who made sure that my father could go to high school in Malmö and finish it. Then he came to Lund and studied philosophy. And eventually, he became a priest.

His background was not very priestly and religious, but he had a grandmother who was very devout and had influenced him quite a lot. Being a priest was the fastest way of becoming something. By doing so, you could be a teacher or something of that sort. But he wanted to continue with his religious studies, during which he met my mother. He always had the ambition to read more, study more, and he eventually succeeded in becoming a Doctor of Theology, but then he was already an elderly man. I guess that was a disappointment for him. Although he naturally was someone who had significant interests, and it is quite important to me that he also had a considerable interest in philosophy.

And it’s clear that as a child I was strongly influenced by the church and the Christian elements, but I had such issues with faith. Right from the beginning, really. I have struggled with it for a few years until it finally disappeared. My father wasn’t happy about it, but he thought it was good that I continued my studies. I had all the opportunities to do so. But in a way, it was a golden age when I started at the university. At that time, there was a program called licensing scholarship, which was tax-free. We didn’t receive much money – today it seems a bit ridiculous – you’d have 333 SEK (approximately 30 EUR) per month. But you could live on that.

I already wrote a bit for newspapers and had been earning more money, so I was relatively wealthy at the time, compared to how I grew up. All my life, I was confronted with big financial problems due to my father, which was sad for him. He came from a poor background. My house wasn’t poor, not really, but there were constantly new debts, and new loans and only when he fell ill with diabetes did my mother finally take over the finances. She previously demanded that she would be the one to run the housing finances, so eventually she did. She became a strict housekeeper, and the situation got better for us. But for me… I think I was fifteen years old at most when I decided: I will never get into such financial problems, right? The whole thing was so engrained in me. I took out a loan at the beginning of my studies in Lund, but then I got what was then called a “nature grant”, which meant that you got one meal a day. So, it was something you could get quite simply if you had decent grades, and because I had finished high school as a private student, I could get it. And at some point, later, I got a “licentiate scholarship” and then immediately a doctoral scholarship.

Wedin: But the licentiate scholarship was to write your thesis, which you wrote in philosophy. But what did you get before that? You called it a “nature grant”.

Liedman: Exactly that.

Wedin: Did you get another scholarship? Or was it your parents who financed your first years?

Liedman: No, they couldn’t pay for anything, no.

Wedin: Okay.

Liedman: Absolutely not, not a single dime. Not more than when I was at home and living there sometimes, but no, it was… I simply paid my own way.

Wedin: From the beginning of the university?

Liedman: Sure, but I had this scholarship and then took out a small loan, and then I got my bachelor’s degree very quickly. That is already sixty years ago.

Wedin: But you had the ambition to have a B.A. before you were twenty.

Liedman: Sure, I also remember studying psychology and pedagogy… I remember reading one of those American books on youth psychology. I read that intelligence was the sharpest at the age of twenty. I remember this was a few days before I turned twenty and then I had this sadness that it’s all going downhill from now on (laughs).

Wedin: (Laughs).

Liedman: But it was a belief that existed at that time, and it was similar to the idea of brain cells dying all the time and you having fewer synapses. Things were like that in those days, because it was as if you had made it to twenty, and now – unstoppably – the brain starts to shrink. And it’s amusing that it was a certainty sixty years ago.

Wedin: Hhm. Yes. What you’ve obviously believed back then.

Liedman: Sure, I remember this sadness – now I am twenty years old, now it’s “Pfff”.

Wedin: Now it’s done.

Liedman: Yeah.

Wedin: Do you remember your first trip abroad? What memories were you left with from that trip?

Liedman: So I was in Denmark with my parents shortly after the war. It must have been shortly after the war, because Denmark was still marked by the conflict and had stayed like that for several years. I remember that. Afterwards, it was only 1956, we went even further away from Sweden, to Germany. I was also in the company of my parents and 17 years old. My brother was there as well. It was still a Germany scarred by the Second World War; many houses were destroyed, abandoned properties. It was interesting. An exciting trip.

Wedin: Were you in northern or southern Germany?

Liedman: All the way from Hamburg and down to Flensburg and as far as Munich. So, this trip, it was important to me. Later on, when I was on my own, I went to a Cours de Civilization in Strasbourg. The teachers I had then, only later did I realize that they were big and famous. So, I attended lectures from both Henri Lefebvre, the great specialist of 1789, and lectures from Paul Ricoeur on these Cours de civilization. They didn’t make a strong impression, because my friends and I didn’t know who they were. The names of the old timetables did not really come with explanations. But it was an experience. I met people who came from all over the world for this course.

Wedin: How old were you by the time?

Liedman: I had just turned 19, I think.

Wedin: At the time you had already studied for almost two years, one and a half years?

Liedman: Yes, I studied for a year and a half.

Wedin: It was one semester when you studied this course of civilization, right?

Liedman: No, no, it was six weeks, altogether. Like summer school. It was a lot of fun to take part in typical French exercises like explication de texte. There we went through the first aphorisms of Jean de la Bruyère. The lecturer was a man with a dramatic appearance: he was a soldier in the world war and almost had his entire chin shot off.

Wedin: Wow.

Liedman: He was always extraordinarily stiff and frozen. Even on hot summer days, he would come with a coat. But he was an excellent lecturer. This is one of the things I remember best. And then there was a man called Cannivait who talked about surrealism and existentialism and topics like that. I remember him talking about Kierkegaard all the time like “Le grand Danois”, which means a big thing for a Swede (laughs).

Wedin: (Laughs).

Liedman: So, for me, le grand Danois isKierkegaard!

Wedin: What does the term “home” mean to you?

Liedman: Home! In a way, it’s a relative term. But that is what every human has to sink into with their everyday lives. And one could say, where there is daily life – there is a home. But the meaning of the term can change. You have an earlier home in your childhood, and as you grow to be a young man, you have a more volatile home: you live in different places and maybe live with a girl or something. I mean, you get a very stable home when you’ve got children, which I got relatively early with my daughter being born in 1964. I was 25 years old when she was born. And that as well is a considerable change in the life of a young man. Then it just becomes a home, because you have to create one for the child. So, I and my then-wife lived in Lund at first, but then you couldn’t get an apartment there if you had children. Where we lived, it was actually forbidden to have any. We lived half a year with children without permission, so we had to buy a very modest house out in Staffanstorp. Which now is a fateful name, with the Swedish Democrats (a far-right political party in Sweden) in the board of the city and in the community. But back then it was an old farming village where they had just started building. So, we lived there. Up here in Gothenburg, I did my dissertation because the history of ideas was here.

Wedin: You were twenty-seven or twenty-six?

Liedman: Let’s see… it was 1966, so I would’ve been 27 at the time.

Wedin: It was spring?

Liedman: Yes, it was in the spring. Oh, but then we, my then-wife, I and our little daughter were living in Staffanstorp. And then when I had finished my dissertation – I got a lecturer’s degree – there was no place where I could apply. At that time, lecture services did exist, but the only one available was an extraordinary lecture service. When I had written for newspapers, especially for Sydsvenskan in Malmö, I was suddenly offered becoming an assistant cultural manager, as it was called, at Sydsvenskan in Malmö, a relatively large and successful newspaper, but perhaps not quite suitable for me (laughs). I was a little too radical for it. But it was inspiring, and I ended up working there for about two and a half years. Actually, I had it pretty nice there, but at some point, there were more and more conflicts. It was 1968 (laughs).

Then different things happened. First, I got a job offer. A lecturer had come to Lund. He had obtained his lectureship when I had defended my thesis. But then he was going to leave, to have a so-called sabbatical and he wanted me to fill in for him. I was spoilt for choice: Would I give up a permanent position and take on a teaching job? My wife at the time said “absolutely not” – you have a security here at your current job. But nonetheless, I quit and left. And then everything was so unclear to me about the appointment of the lecturer at Lund University (LU). Later I jumped in as teaching fellow for Henrik Sandblad for several months in the spring of 1970. And then back to Lund, but then there a position as extraordinary lecturer in Gothenburg was advertised, and I got it.

Wedin: Exactly.

Liedman: And in January 1971 we moved to Gothenburg.

Wedin: But when you moved there – the Masthugget district wasn’t your home since the beginning. You moved around quite a bit.

Liedman: So, we thought we were promised one thing, a small house where we could live, quite well in Fredriksdal, because the man who owned it was about to marry someone in another place. Suddenly it was broken off, and his marriage didn’t work out. Then we rented for a time and finally got an apartment in Örgryte… it was called Barrskogsgatan. That was fairly difficult. The environment did not suit us at all, and my daughter, who went to school at the time had the wrong dialect for it. She spoke Staffanstorp dialect, and suddenly it was this somewhat finer Gothenburg dialect that applied there. It wasn’t that easy for her, and we had a son who was almost three years younger. And yes – both of the children had difficulties with fitting in at first. The department here in Gothenburg was wonderful. Sandblad had built it up – out of nothing really. And then, there were a number of persons who at the time contributed to this and made it so good. It was very comfortable and pleasant. At this time, I felt good, but there were problems with the children: It’s no fun if the kids aren’t happy and have a longing for where they lived before. As time passed, certain events took place; among others, I met my now-wife; this is many, many years ago, pretty much in the early seventies. Then everything rolled out like this: first I had gotten a divorce, and then I married her. She and I had a third child, a son. And later we got a new home, and we were lucky enough to get an apartment on the top of Linnégatan; at the time houses leaned, they had been built incorrectly around the turn of the century and to tilt more and more. Still, we lived there for five or six years. It was a beautiful apartment, but destined to tilt and break, which we didn’t know from the beginning. But when there were actual demolition warnings, we had to leave with three children still living at home, and it merely became this apartment in Masthugget. This is where we still live in, my wife and me.

Wedin: Yes, the same year I was born in.

Liedman: The same year, you were born? Yes.

Wedin: You grew up in a family of priests in southern Sweden. Do you feel that your family left room for doubt regarding being a believer?

Liedman: Yes, my father, he was very much like that… he had read a lot of Luther, and what Luther wrote about doubt, which is omnipresent in his writings. So, he was open to the concept of uncertainty. But I do remember being shocked when my grandmother died. And she died at home with us, so she laid dead in our house for a few days… it wasn’t strange back then, as a priest’s child in the countryside you got so used to death. Hence it wasn’t as unusual as one might think, but I remember this question floating around: How is she doing now? And then I remember my mother, to my amazement, first saying, “We don’t know.” So my father went and got Luther’s big postil, saying that the dead man should expect the judgment “mit Furcht und mit Beben” which means with fear and with trembling, and it was, you could say, my own doubt, but there (laughs) is so much more of it, isn’t there?

So, my father was, one could say, a representative of the low church. Although politically rather conservative, he was, for example, in favour of female priests. He was a very early supporter of the comprehensive school – which then became a basic school (the Swedish comprehensive school system) – but his faith was more of this little low church, sentimental kind, a little pietist almost. My mother came from a family that was very active in the Swedish Evangelical Mission (SEM); it was like a lower church. But a place for doubt: I became much more doubtful when I was 16 years old. Later on, I had a girlfriend for a few years, my fiancée at the time, and she was a true believer. I did try to stick with it, but when it ended – she ended it – when she came to Lund. She was a few years younger than me and I was already quite far away. And it wasn’t funny when it happened, but I remember the feeling: but my God, now I’m rid of all this, I don’t have to try to pretend I believed in it. Or to pretend I didn’t do, but still, having it as a living reality. I can say that I still give great importance to tolerating religiosity – no matter which religion it is – and thus tolerate all other religions and non-religions, but I never miss it. I know many who left [the church], who came from similar backgrounds, who are as old or practically as old as me, who miss the religiosity, but I can’t say that I ever did. What first and foremost took religion’s place for me when I was a little child, was literature. Music certainly played a similar role, and so did art sometimes. But above all literature: that there exists such an immense richness of expressions and the register of emotions and everything, yes – for me it was never problematic without religion. As I said: respect for all sincerely tolerant religious beliefs, but I don’t have it, and I don’t miss it.

Wedin: No, you perceive that you have had, risking sounding trivial here, a source for this kind of energies?

Liedman: Yes, elsewhere, yes!

Wedin: How did you deal with your beliefs and expectations regarding your children?

Liedman: My father had very high expectations for us, which were probably a bit too big. It was so funny (laughs), for me it felt that I had somehow (finally) fulfilled what he had expected of me when I became a professor. There were two things; he had never had a daughter of his own, which he wanted very much. I got the first thing, because I had a daughter, whom he naturally came to worship. The second thing was that I became a professor. I became one before he died. He was a heavy diabetic, but he experienced it and was obviously very happy about it.

Wedin: Did he also have the ambition to write?

Liedman: Yes, he had the ambition to write. That’s why he encouraged me to do so. I had it pretty early, I had a kind of kookiness when I was barely 14 years old. It happened to me as I studied at Hermods instead of going to a regular school, where I discovered literature: I began to read like I had never done before, masses of books. And then I started to write too, but he encouraged it anyway all the time. After all, he didn’t like what I wrote; with that I mean my tendencies, political radicalism and topic like that, but he thought it was nice that I did it in general.

Wedin: You write in your memoirs that the way you discovered that reading can be exciting is through Frans G. Bengtsson’s memoirs “Den Lustgård som jag minns” (The Garden Eden that I remember), which you read in the same year it came out, that is 1953. When you read the same book much later, were you not impressed [anymore]? What appealed to you about this specific book at the age of 14?

Liedman: I don’t know, after all it’s a children’s and young people’s narrative. This “Garden Eden that I remember” is pretty straight forward. I could probably identify a little bit with it myself. The poems are about a sort of garden, and we had a large garden at the time which we no longer had access to in Vittskövle… it was probably the garden which reminded me of my own little “Garden Eden”. And then, of course, the discovery of how much fun it was to read. I may have experienced it when I was a boy, but even many years later, I had this almost unpleasant urge to read.

Wedin: But if I understood correctly, it was a coincidence that it was this specific book?

Liedman: It was a coincidence, yeah.

Wedin: So, it could have been any other book?

Liedman: It could have been any other, but it became this one. After that, I started reading the next book, which I think was by Harry Martinson. And then I went on reading French novels that made me have ideas about Paris without ever being there.

Wedin: You mentioned earlier that you studied at Hermods and that you studied by distance, and later graduated as a private student. Also, you wrote that during that time you had – and I’m quoting from your memoirs here – “Excessively optimistic, long, complicated work schedules”. Can you tell us what a typical school day looked like during this period of distance courses, and please specify your age, you were there between 14 and 17?

Liedman: Yeah, it was from 14 to 17. Well, at Hermods, there were these small notebooks you received, and each course consisted of a certain number of these booklets, it could be 5 or 10 or 20 or 25, and then we just studied through these. Maybe I studied and had a little break after and in the afternoons, I read something else and then – because they were separate topics that we had to learn about at the same time – you had to test them individually. But otherwise, I had deadlines to finish this or that topic, which I had to get right because I studied on the Latin program that I wasn’t really keen on because I thought math would be more fun. But to study literature and philosophy – literary history it was called back then – you had to study in the Latin program, you needed Latin. So, I chose it, but later I also got tested in math and physics and chemistry and biology and geography, which I couldn’t get earlier. In the degree there was testing subject by subject, and then in the following examinations, you had to major in a specific subject. I did history, and later on Swedish, and when I was done with Swedish, I remember getting a pipe because back then I still thought a man should smoke pipes. I started because of that and went on for more than 20 years before I quit.

Wedin: Do I understand you right, you studied from afar, and because of that you studied each subject in a more concentrated form, in chunks and focused on one thing at a time?

Liedman: Yeah. In the beginning, I read many subjects in parallel, but I just had to focus more. And it was actually nice, and I felt good about it. You learned, but you also understood how to manage different learning techniques, which I was still able to use when I started university. Many of those who came from regular high schools were a little afraid to read such big books suddenly. But for me, it was pretty simple because I had been sitting there with all those texts for years and I thought I had a proper preparation.

Wedin: You also mentioned that in Vittskövle there was at least one teacher, or a substitute teacher in fourth grade, called Gunnel Nilsson, who played an essential role for you. Can you tell us something about why and to what extent she was important to you?

Liedman: The background was that back then, I had a difficult teacher. It became particularly hard for me because of my father. He had these aspirations that because I had learned how to read, I should skip the first class, and the teachers weren’t really fond of that. Later I had it a little more comfortable in third grade, and the fourth grade was very pleasant for me. We went to the old post office in Vittskövle, and this teacher was young and had some familiarity with us. We were divided into small classes. In my class there were like six people. It was a rather old-fashioned school. But it was a nice year. Later I met her again by chance. I gave lectures in my home district; they had ordered a lecture. I would talk about (laughs) my course form. What was it again – Vittskövle to somewhere? And then I spoke about my fourth grade and Gunnel Nilsson, which is not so long ago.

Wedin: Could it have been 2006?

Liedman: Maybe. In any case, an elderly lady came after me and said that she indeed was Gunnel Nilsson, so she had heard that I was there by chance, which was a total surprise for me. It was strange. She had retired by then, but before that she had moved to become a teacher in Saltsjöbaden.

Wedin: Okay.

Liedman: But she started her career in Vittskövle, with us, at the post office.

Wedin: Because she was around 30, she must have been relatively old.

Liedman: She wasn’t that old yet, maybe a little over 20. I remember that she had a fiancé who sometimes showed up when she was teaching us. They made the whole class giggle (laughs).

Wedin: What languages did you learn in school? Did you have a particular relation with one of them? If so, do you remember why?

Liedman: The languages I learned were English, German, French and Latin. I continued after graduation and learned a little Greek, and because I completed that course later on, I learned elementary Greek. But otherwise, these were the languages. One could say that I had an unfortunate relationship with English because I had a teacher whom I didn’t like very much in Kristianstad. At first, I didn’t like German either, only French.

Wedin: Are we talking about high school now?

Liedman: Yes, exactly. I only had French later on, before I finished school. So that’s when I found my “true self”, so to speak. I remember I thought that French was a fascinating language.

Wedin: During the times at Hermods?

Liedman: Yes, in the Hermods times French simply was the thing. After 1933, French was the most crucial modern language in high school. It was the major modern language in high school. You would only write in German or English for a few years. So, it was in French. Then Latin became the new issue because there was so much of it. For example, at the high school I didn’t go to, it was seven hours a week for four years. Seven hours a week for four years! It was a lot: you had to read many thinkers such as Caesar, Livius and Cicero. After that, you would continue with poetry. I loved it. Back then I knew a number of pieces by heart. I am less sure how it is nowadays. But I learned to adore Latin poetry back then. It was a great experience of poetry. Ah yes, Latin! Then, for a long time, I couldn’t really enjoy having studied Latin, but some thirty years back I started to appreciate it again. It’s not something I’ve systematically kept in repair, but I have been able to read dissertations from the 17th and 18th centuries, and I find that amusing.

Wedin: I understand that. Do you remember what you bought with your first salary in addition to food and necessities?

Liedman: My first salary when I started working?

Wedin: Yes.

Liedman: So, at Sydsvenskan, 1966. I believe that my wife and I were out buying clothes for the kids. Or it was one child back then, yes.

Wedin: The child, yes.

Liedman: That was certainly the first. So, something you got enough of if you worked on the cultural editorial, at least at that time, were books. It was just the time. I mean, now it’s hard to imagine that publishers, even as big as Anglo-Saxon publishers, sent out editions of their works. I mean, I remember that in the editorial office at Sydsvenskan I could pick up the new edition of Locke’s “Two Treatises of Government”, a new critical edition from the 60s – and there were many books like that. Even all papers by Søren Kierkegaard, so it wasn’t just Swedish literature. And when it came to academic literature, most of the time, I could take exactly what I wanted. Hence, there were many years I hardly ever had to buy books.

Wedin: You got them via what?

Liedman: Via the newspaper. That’s certainly not how it is now. These big international publishers, they stopped sending these books a long time ago. I think it ended around 1970, but by then I had stopped working at the newspaper, and it’s interesting, that those are many, many of the books we have.

Wedin: From that time?

Liedman: Yes.

Wedin: Given the considerable time you have spent in your life thinking about Karl Marx‘ thinking, in particular the role the term “work” played in his thinking, I wonder how you see the meaning of work for humans?

Liedman: Well, I think there is, as with Marx, as with his predecessors and as with many of the great German philosophers a certain view of mankind – a kind of philosophical anthropology – which says that humans are social and active beings. I think it’s beautiful and such a contrast to Adam Smith, for whom humans are always driven to work – all kinds of work. For Smith, humans are by nature, indolent and passive beings; there must be impulses or compulsions for them to work, but for Marx, humans are active beings – just as they are social beings. One is not born as a person, you can possibly become one in life (laughs), but always in your exact social context. But considering work, Marx differentiates between the free occupation, so, being able to fulfil yourself and getting an exit for one’s creative energies. And forced labour, meaning being forced to do something. Industrial work, therefore, gives workers a choice: Either to starve or to accept the job. It’s the situation the workers represent in this case. And for Marx, the hope is that humans will understand this, and it will enable them to operate freely. And it’s essential to remember that to operate freely in terms of Marx is not to do a little something on the side, a little here and a little there, or just being idle. Marx writes that, and this is something I’ve often quoted and that I still love from “Grundrisse” where he says, that completely free work is like composing. Like one can compose music, he probably thought about composing Das Kapital. Which he did, and it must have been the most intense effort and the most cursed earnestness at the same time. So, when you decide to compose a project, you decide on something you think you want to do. Once you’ve started, there’s a lot of compulsion. Whatever we do, it is self-chosen, there is an enormous attraction in the whole idea, but it’s a fact, that if you understood it a little bit, then you have to do it. Then you’re forced to do it, I do it, then I have to do it, then I do it, and it just goes on like that. Then there is this seriousness and this intense effort. I think it’s a lovely picture of a good human life, isn’t it?

Wedin: It’s a kind of inner compulsion that arises from free creation, and through (laughs) this inner compulsion also a severe serious relationship to work results. This devotion.

Liedman: Sure, the devotion, it’s a good word “devotion”.

Wedin: It makes perfect sense to immediately connect your statements with your long-standing commitment to school-related topics and the concept of Bildung, and what you told us about your thoughts on the role of work. Would you like to elaborate on how you see the connection between these two, the importance of work for people and the idea of Bildung?

Liedman: A Scandinavian tradition I find very beautiful is something called folkbildning, it’s like an accessible education. It’s mostly an idea, unfortunately not being as alive today as it used to be. However, it’s about broadening the horizons of all people, who, even though they remain in their forced labour, can expand and move towards more and more freedom. And that for me is Bildung, which finally should be a way to freedom. The definition of freedom, on the other hand, used to be very different from what it is now. As freedom of choice, for example; freedom of choice is of course, connected to the warehouse. I mean, I think it’s nice that there are a lot of goods in the warehouses, even though half might be enough. But the real freedom is the freedom that arises when you are yourself, or perhaps in projects with others – it’s so important to remember that you are able to work together, to have a common goal. Let’s say a research project is one of the important ones, and in the best case, you work with each other, and yet everyone – everyone – is fully involved. For me, education has two sides. You always have to get involved with certain things. You must specialize, meaning spending a lot of time with scientific specialization – but whatever you do, you must specialize in it and in this free activity you must dig deeper and deeper, without losing sight of the broader perspective. For me Bildung is the combination of these both things, the vast horizon and this intense digging into the details, both should be there in a fulfilled life.

Wedin: So, it’s an analogy to the work; one could describe it as the inner compulsion, that is the digging.

Liedman: Yes, of course, it’s digging. It’s essential to see that this is my piece, but that there is a bigger picture. I mean, I try as hard as I can to keep up with certain things when it comes to science, for example, which I always find fascinating. Anyway, I think it’s not my area. But I have always had an interest in biology, and above all my passion as a young boy were insects, because I was so near-sighted. At that time, I was very near-sighted (laughs).

Wedin: You had an uncle.

Liedman: Yes, on my mothers’ side, he was really a step-uncle. He was a teacher of biology and chemistry, and he was mainly interested in birds. I would have been too if I hadn’t been so near-sighted (laughs).

Wedin: (Laughs).

Liedman: Only when I had surgery some years ago, regarding my cataracts, the short-sightedness was removed, and new lenses were inserted. And suddenly the vision in my left eye, in which I was extremely near-sighted, was restored and this was so peculiar for me; I remember my wife and I were outside and took a walk where we have our country house in Skåne, and then she said: “But look, that bird there looks like a canary.” And for the first time in my life, I saw a yellowhammer.

Wedin: (Laughs).

Liedman: It was a fairytale-like experience. I’ve known what a yellowhammer sounds like since I was five, but to actually see it. And now I can see, so suddenly I can see a European robin and the difference between a robin and whinchat. I think it is fun.

Wedin: In your twenties, were you optimistic or pessimistic about the future? Compare yourself at that age, at the age of 50 and now when you’re about to be 80 very soon.

Liedman: Yes, what does it mean when you’re 20? I was 20 years old in 1959. It was a time when you were terrified of a third world war. There was a constant tension between the superpowers that existed at that time: the USA and the Soviet Union. So, all along, there was this thought: It can go completely awry, and the world can stop in a few moments or a few years. But at the same time, there was the idea that if it wasn’t going to happen, you still had a pretty bright future ahead of you. Now there are conversations in France about the 30 golden years after 1945, and that time was right in the middle of them. This feeling could almost contain a little bit of sadness sometimes that it’s almost too good. The world was moving forward: Sweden’s economy was growing, more and more holiday weeks were being spent, new technological inventions were continually coming, and we even got television. That’s how it was when I was twenty. When I was 40 years old, 1979, then we are in the middle of my life. Or, you asked about my 50s, sorry.

Wedin: You can also talk about the 40s.

Liedman: Back when I was 50, I had just received my professorship here in Gothenburg, I was doing very well privately. I was quite optimistic about what I wanted to do, at the little Department of History of Ideas, and I had wild plans for it. Back then, it was still quite tense in the world, but in a slightly different way than earlier, and then it increased slightly. 1989, I turned 50 in the year the Wall came down. I had spent quite a lot of time both in the old GDR and in Poland and some places in the Soviet Union, and I have to say that the development, especially at the beginning, I found to be very hopeful. I thought, that this neo-liberalism, which came up in the 80s, would be counteracted by the fall of the wall, but on the contrary – it was deeply strengthened by it, and things didn’t turn out the way I had imagined. But I was optimistic and thought that we could get a form of reformistic democratic socialism then. At hindsight, that might even seem a little naïve. Now, that is 2019 when I (laughs) am 80 years old – well, it’s like that. So, it’s fair to say that as far as I am concerned privately, I am doing just fine. Relatively healthy, only a few problems with the joints and osteoarthritis, which probably were intensified by running marathons and half marathons. But that’s all, after all, I have osteoarthritis, but for what I know that is the only health problem – at the same time you know that you’re so old (laughs) the finiteness of life is so very tangible. But I cannot say that it worries me much, I fear that I get debilitating diseases, but I cannot say that I worry. It just goes on. You lived your life.

But I can say that the world, that’s something you didn’t have… just about exactly when the greenhouse effect became a thing. I remember there was an U.S. American giving a lecture in theory of science somewhere around 1989. Today it’s the all-dominant subject, and fateful. For one, we see that there are enormous demands that something has to be done quickly, and at the same time there is resistence by leading politicians, leading large companies, even leading trade unions and thus the essential colossal change – they are not ready for it. That makes me anxious – not for my own sake because I’m sure that I can get away before anything happens. Still, I have not only children and grandchildren, but even great-grandchildren, the youngest is just over two months old, and so it feels like overlooking their lives. So, how will it be? And then there is also the world being ruled by foolish people, Yes, Trump of course, but many others too. Putin is a bad guy with cold temperament, and Xi Jinping is undoubtedly the brightest light of them, but I mean, China. It’s this combination of communist command and raw capitalism, which is not really fun either and we have so much of it. Generally speaking, this is what I think it looks like today.

Wedin: If you want to summarize it, then you have gone over to see the future more and more pessimistically, concerning the big thing.

Liedman: The big thing today is the climate and the environment in general. The environment was also crucial for the 80s, 70s and 60s, when Carson’s “Silent Spring” came out [environmental science book published in 1962 documenting the adverse environmental effects caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides]. I remember it was terrible, wasn’t it? And it even looks darker today than it used to. But you have to remember that when I was born, my first years were during World War II, which was terrible, even though I couldn’t see anything of it.

Wedin: It was present anyway, but in a kind of abstract.

Liedman: The war, yes, there it was. This huge house we lived in was near to the east coast of Skåne: it was where the Russians would disembark, it was mainly that. But there was military, a lot of militaries. So, this big house of ours had at the beginning, I think, seven of the rooms occupied by people from the military. Then it was reduced to four, and they had access to our stables – it was an old rectory with large outbuildings. I remember the constant fight between my mother and the soldiers who wanted to put their horses where she had her chickens laying eggs (laughs). I remember that they quibbled over this. I was about four years old.

Wedin: How has your perception of Europe changed over time? Once again, I’d like you to make a difference between the age of 20, under 50 and today.

Liedman: Yes! In my twenties: I was 21 when I visited Berlin for the first time, and there was a very intense feeling of Europe. This was before the Berlin Wall: you could walk between East and West. I worked on my licentiate’s dissertation back then. I wandered in between – it was just when the Soviet shot down the U.S. spy plane U2, over Siberia, and it was incredibly tense at that time. Then the Cold War began in Berlin, and the tanks stood on both sides of the Brandenburg Gate, united in the division. I experienced it more intensely when I was almost 21 years old. It was like a picture of Europe at the time. I had been to Strasbourg two years earlier. There I had seen a picture of a divided Europe as well. And one does not get away with the fact that there were still such clear traces of the Second World War in Europe – not to mention in Berlin. Especially when you came further east, it took a few years until I came further east in terms of Europe. But that was my picture back then. When I was 50 years old, it was this idea that now we will receive a new and better Europe.

Wedin: Did you share it?

Liedman: Yes, I did share it. So, I was surely not a supporter of the EU, but there were very few in Sweden who were in 1989. There was a small minority on the right. But I thought that now we could have a better Europe. A Europe also in relation to the world in general, it was essential to have these ideas, even though it was a bit naïve to think that Europe could provide a cultural counterweight to the United States. This soft power of the U.S.: there was this idea that Germany in particular would have an immense cultural significance after its reunification, powerful and central and all of that. But it wasn’t like that, was it? So, I was an opponent of the EU when Sweden was supposed to enter; I voted no. But I still think that there is something important in the EU, that we could get some form of what is today referred again to as democratic socialism. This is my dream. And here I can say that the developments in the USA, not least the anti-Trump development there, fascinate me very much. I have no idea yet how far all of this will go, but when my book came out with the publisher Verso in Brooklyn, New York – and thereupon celebrating the 200 years anniversary of Marx’ birth – hundreds of people, most of them very young, showed up and later discussed my book. Something was fascinating about it; you could feel the commitment. Someone like Alexandria, now I lost her name.

Wedin: The young democrat?

Liedman: The young democrat with two surnames (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez), what a person – it is fascinating to me that there are such people, with such very far-reaching radical proposals. Not only in terms of health insurance, but also in terms of school and education. I hope that some of this energy will come […]

Wedin: And infect Europe somehow.

Liedman: That as well: a lot of things come from the USA, why not this as well? I mean, when we get someone like Trump, we could get something better as well.

Wedin: Yes, one can hope for that!

Liedman: One can hope!

Wedin: Did you ever feel like you were the enemy in other people’s eyes?

Liedman: Yes, I felt that sometimes. You get that because my profile has been associated with the left side, you can say that some have regarded me as an enemy. I mean, you can see it today too. For example, there are the Swedish democrats and extremists with right-wing nationalistic ideas. They don’t dislike me personally, because to them I am like them, an (laughs) old man, and they don’t have to fear me. But they find what I stand for incredibly disgusting. And there are some other things they don’t like either. It’s more like a general feeling. If you are one of these white middle-class men, then you are so protected, in terms of many different types of hate. No one sees that immediately: this, this is an enemy, like a Muslim, for example.

Wedin: No, it’s more like you are describing it as being abstract.

Liedman: Yes, it’s more abstract, it’s for what you stand for; for what you want to do, what you want to work for. It’s disgusting, but oneself, well.

Wedin: But not as a person made of flesh and blood.

Liedman: No, no.

Wedin: Do you see the many conflicts in Europe in the 20th century more like a European matter or more like singular national conflicts?

Liedman: The interesting thing about today’s nationalism is that it is not only powerful in Europe, but it also exists in India, in the USA and more or less anywhere really. But while the nationalism that flourished around World War I led to both world wars, one can say that nationalists were enemies: French against Germans, Germans against Russians, etc. You might be friends with your enemy’s enemy, but (laughs), but you can never be a true friend; you were only for your own nation, while contemporary nationalists form a kind of informal, formless internationality, right? It’s like, Bannon he can go […]

Wedin: To Hungary?

Liedman: Yes, to Hungary, or Italy and try to build a kind of network with extreme, extreme nationalists in different countries, that is a massive difference to the old nationalism. I have come to take an interest in Indian nationalism, Hindutva [the predominant form of Hindu nationalism in India], it is the first of its kind to breakthrough like this, and it is also interesting that under Narendra Modi and his BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party), they have adopted a method in which neoliberal politics are a unification band. Before he and his party came to power, it was different. An economy for India’s industry would be protected externally, but then it was opened up. So now there is a great difference: nationalists nowadays are, so to speak, joined together into a kind of unholy brotherhood.

Wedin: So, the major conflicts in the first and second half of the 20th century – you consider them being structured by a national logic of a different kind, which motivates one to see them as domestic conflicts. But if you link it to Europe, [considering] that these were European conflicts: How do you see the relationship between Europe, the history of Europe and this history, the power of nationalism – in the past and now? Because you said that there is a difference.

Liedman: There is a difference. They will hardly go to war or try to go to war with each other under the given circumstances. That’s definitely not the case. They continuously say that they are fighting internal enemies – country by country. After all, Islam is the worst internal enemy, and it’s funny, because the pattern is so clear there, in India, where there are somewhat like 160 million Muslims. But in Sweden as well and also in other countries, France, for example, for the nationalists, Islamic people are now the greatest enemy. But then again, so is liberalism and socialism, and to a large extent also feminism, which are enemies because these are quite modern projects that they consider left. They always perceive the Left, so liberalism, much more like liberalism in the United States, not so much in Europe. The left in the United States is liberal, which means you have a vast field towards the left as a liberal in the States. I mean, they are not enemies, because they represent different cultures, but because they represent the wrong cultures: an internationalism, globalism. Of course, there are clearer and clearer strains of anti-Semitism in this. Globalists – it is George Soros who is the great liberal.

Wedin: And there are also evident characteristics of continuity, even if you go further back.

Liedman: Obviously, yes!

Wedin: Are there politicians – contemporary or from the past – that you admire? And why?

Liedman: Yes, there are some I admire. If you want to speak about someone whom I met quite often as a young person in Lund, it was Ernst Wigforss, the former Swedish social democratic finance minister, who at the time was more or less as old as I am [now]. He was almost always at the philosophical union in Lund. After all, he had studied and lived in Lund and was a somewhat impressive figure there. But I’ve come to study him more and more. In 1908 he wrote a book on the materialistic view of history, and also his memoirs are fantastic. So, I read his books, and I think he has something solid and lasting, something with enormous consequences. He writes about radicalism, which refers to one of the greatest dangers of our time and the growing class divisions. He had accomplished many things in Sweden which have been thwarted since. With taxes on wealth, inheritance and real estate. Suddenly Sweden has become a paradise for the rich, and that destroyed his work. I kind of hope for a new Ernst Wigforss. Well, but there are many that I think are impressive. I find this new American West to be fascinating. Bernie Sanders, he is an, uh, older man, he is almost as old as I am, so he is not a real promise for the future, but something has to come out of it. I think – Ocasio, she’s called. I think there should come something for the future out of this generation, which is now 25-30 years old or maybe even younger.

Wedin: Have you had any rituals in your life?

Liedman: Rituals?

Wedin: Yes.

Liedman: (Laughs) yes. Even with my age, I’m actually doing gymnastics every morning and evening, (laughs) they are my rituals.

Wedin: That’s something you’ve done all your life?

Liedman: Not really, but almost half my life, I did morning gymnastics, with which I keep myself reasonably fit. It gets more and more important the older you get.

Wedin: Yes.

Liedman: It becomes more and more challenging to balance exercises with everything else. But those are probably the rites I have. And to take walks: Walking is extremely important in my life.

Wedin: Did you do walk a lot or ran as well?

Liedman: Not really, but I walked – I walked most of the time from and to the department, it’s a few miles or so.

Wedin: Is there a piece of art – a motif in the visual arts, a literary work, a piece of music, a film or something else – that has meant a lot to you? If so, how?

Liedman: Yes, there are so many, it’s hard to say.

Wedin: “Bortsett” by Frans G. Bengtssons (laughs).

Liedman: No, I don’t think that it held its ground, but I can say Dostoevsky’s novels have, they really have. That was one of my first big reading experiences. I don’t know if I was even 16.

Wedin: Something specific?

Liedman: It was Raskolnikov. In our translation, the book was called “Crime and Punishment”. The book just caught me. I remember that I lost track of time, and suddenly it was morning. It is one of the most exceptional experiences.

Eva-Marie Liedman enters: The may bells are blooming already.

E-M: Hey, Tomas.

Wedin: Hey, Eva-Marie.

Liedman: Where were we?

Wedin: Crime and Punishment, 16 or 17 years old.

Liedman: I was 16, couldn’t have been older. But it was an incredible experience. I’ve read it a few times and by the way, in general, they still hold up; Dostoevsky’s novels. As a child, in my younger days and even later, I really liked Thomas Mann, especially ‘Zauberberg’. He is so nice to read in German: enormous, beautiful long sentences. Oh, that’s true, music also exists. As a child, I had to go to church, and there was a cantor who at that time was a very experienced and modern organist named Bernd Fredrikson. He played postludes, mostly from Bach. That’s why listening to Bach feels like home to me. But since then I’ve been listening to Beethoven, and I also like Shostakovich very much and what else? Right, Artwork. My most exceptional art experience was when I was about 50, funny enough I wasn’t so young anymore, but it was strangeanyway. Eva-Maria and I were in Milan in a monastery, and I saw Da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’, which they just had restored it. They put the finishing touches to it, and after having seen one million reproductions, Warhol’s and all other ones, we were suddenly there faced with it, restored it to its original brilliance, it felt like: This is what it looks like. The actual work of art, not just another reproduction. It was a great experience. I have had great experiences like this, undoubtedly many of them. And there are also many movies. I have had a weakness for Buñuel.

Wedin: Aha – something specific?

Liedman: Yes, ‘The Phantom of Liberty’.

Wedin: Yes.

Liedman: I like that one so much. Absolutely absurd and only displaying fantasies. But there are also many other movies that I enjoyed, and poetry also has played a big role in my life.

Wedin: You’ve even tried yourself in that, haven’t you?

Liedman: Yes, I’ve tried it, but not with great success. I can be extremely fascinated, especially by what I consider an image of human life, for example in Homer’s work and especially in the “Odyssey”. You’re on your way somewhere, things are happening all the time, and then you get home; It’s the very theme of Bildung itself – to have experienced something and to have been immensely enriched. But there is so much more. I read Latin poetry with pleasure; it really was a revelation for me at the time. And then there are many, my God, many. Since my youth, since I was about 19, I have known Göran Sonnevi [Swedish poet] very well – all his books are over there [in the book case] – and it is clear that he has played a significant role for me. And another poet and writer that we have gotten to know very well in the recent years is Kjell Espmark, whose poems I find very beautiful – and of course Tranströmer [both Swedish poets], there is a lot!

Wedin: Yes, I can understand that you could continue this topic for a long time. Has your attitude to freedom changed over time? You can choose anything at any time you wish.

Liedman: Yes, it certainly did. I think it’s a lot of the basics, and that means I got to know German philosophy very early. There were a few, about twenty, that I read, and they were the beginning of a lot of my ideas. And freedom is, without a doubt, a very important topic. I read Hegel before I read Marx, which was very unusual at the time. In particular the idea of freedom in his thought: Freedom is not arbitrary, not “willkürlich”, but actual freedom, well that is what Marx then develops and concretizes. In a way, I stuck with the idea ever since. I’ve certainly had a lot more to say in the past (laughs), about the romantic image of freedom, like the one you have as a child, and especially as a teenager. But this has followed me and has been a central theme. It’s clear, and I won’t hide the fact that indeed, I was fascinated by the Soviet experiment. As it looked from the beginning, I thought it was a possible path forward, but it clearly wasn’t. That was what we were convinced of, and of course, it took a long time to think otherwise because I read so much from these leading figures, I was very taken by it. But it was what you imagined, all of those great projects that supposedly were realized, all this that was supposed to be done together, was only talked about rhetorically, and you, being there, could eventually see more and more how incredibly hollow it was. In other words, it is not possible to simply remodel people. We are capable of development, but there are always some aspects that, in the view of several billion years of biological evolution and many thousands of years of human and historical progress, it seems like the freedom we are actually capable of is limited, right? We still have the same compounds in our heads.

Wedin: You have written a book on freedom and a book on solidarity, but so far, none that is primarily concerned with equality. You wrote that you may not dare or want to because this ideal feels too close to you. Do you find that it is a more central concept than the other two, of the Trinity that we inherited from the French Revolution, and why if so?

Liedman: Well, I think all three are equally important. I wouldn’t classify them like that anyway, but it’s just that my experience with equality is so existential. It emerged already at the age of 10 within me, this experience of being trapped in myself and that I always would be me. So, there’s no freedom at all, nowhere to move. And then it was so incredibly contingent that it was only me with this life story who was born here in this exact environment. That it was me who happened to become me. That I might as well could’ve been someone else. It’s a very trivial thought, but because it’s so existential, it sat deep inside of me and I felt it at all times. I always think of this when I meet people that are severely handicapped, for example, or born into severe poverty. I can feel that it might as well could’ve been me. It’s as if some lucky circumstances made it not be me. I mean, I find it so terrible this hatred towards beggars, given their background in Romania or Bulgaria. Exactly that feeling makes it difficult. I think I probably never will be able to write about equality because it feels too close to me. And this feeling, that I was incredibly privileged in many ways, that I was born in a decent, quiet environment, in a little peaceful corner of the world just like that. To be young in the constructional phase of a country. And then just getting an exciting and fun job, and to be able to devote yourself to your biggest interests is a huge privilege. Like being with a big happy family, you know!

Wedin: It’s really challenging to deal with these things; it’s just like that.

Liedman: Yes, there is something in me though that wishes I could do better. But it’s possible that, as I get older, I will take more time to write about equality, but we will see.

Wedin: Yes… Thank you so much, Sven-Eric Liedman!

Liedman: Yes, thank you! This was funny and enjoyable (laughs).