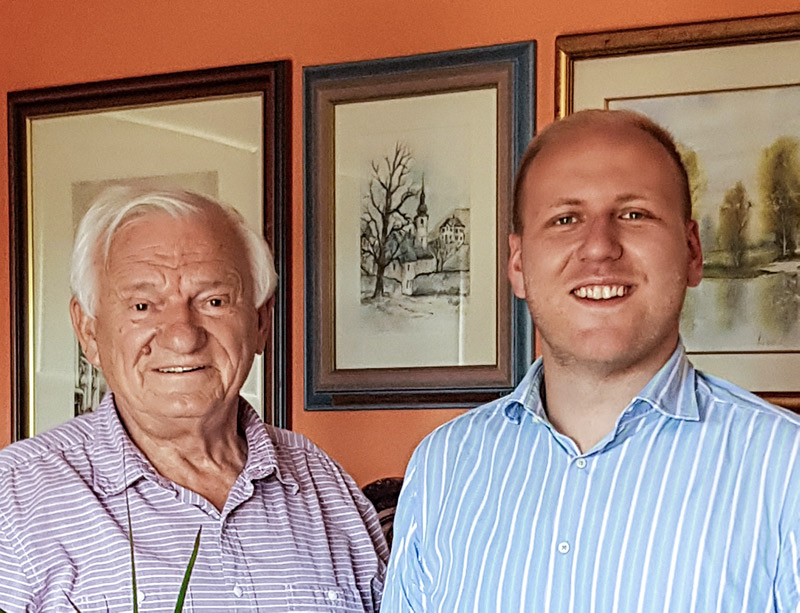

Eldar Shengelaia, born 1933 in Tiblisi, is one of Georgia’s most famous film directors and screenwriters.

He was born into a family of film-makers, his mother a renown actress and his father a film director. After graduating from the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography in Moscow in 1958, he worked for Mosfilm filmstudio – the largest and oldest film studio in Russia.

In 1960, he became a director at the Tbilisi-based Gruziya-film studio. Between 1957 and 1996 he created more than ten films, many of which gained wide spread international recognition, such as “Unusual Exhibition” (1968). Shengelaia’s films are known for their use of irony and allegories, often conveying anti-Soviet messages. One of his most famous movies for instance, “Blue Mountains” (1984), is an “ironic grotesque portrait of stalemated soviet society”. Eldar Shengelaia was also active in politics, including as member of the commission that investigated the Soviet military crackdown on pro-independence rally in Tbilisi in April 1989, and for which he was awarded one of Georgia’s highest civic awards.

In the interview with journalist Nina Kheladze, Shengelaia spoke about his first travels to western Europe, the constraints of making films under soviet censorship, and the future of the Georgian-European relations.

Eldar Shengelaia was interviewed by the journalist Nina Kheladze.

Interview Highlights

On freedom

Kheladze: Did you feel free and safe as a child?

Shengelaia: Me? Yes, absolutely, sure. I want to tell you one thing: Stalin’s regime caused many horrors, disasters, but there was absolute order and discipline.

Kheladze: Didn’t you feel threatened by the purges [against political opponents]?

Shengelaia: In our family, my Aunty Kira was purged. She was the wife of a famous writer, Pilniak. Pilniak was arrested and executed, and my aunt called granny, asking her to come to Moscow as soon as possible, because she was afraid that they would take Boria [Kira’s son] away, as he was two years old then. Granny arrived, took Boria with her. Boria’s surname should be Pilniak, but my granny gave him the surname of our grandfather – Andronikashvili. Boria was living with us, during that decade.

My mother once visited the Kremlin and summoned up the courage to approach Stalin, personally telling him that she had nothing to say about Pilniak, but that her sister was not guilty of anything. Stalin called [Lavrenty] Beria (director of the Soviet secret police who played a major role in the purges of Joseph Stalin’s opponents), and asked him to release her. So, Aunty Kira was released.

1 https://www.festival-cannes.com/en/artist/eldar-shengelaia

2 Political purges against political opponents, often with individuals taken away and ”disappearing” after dark. Familiar phenomenon incl. in the 1950s.

3 They changed the surname to conceal the connection to his father.

On recognition for his work in Georgia and Europe

Kheladze: Have you ever thought that your contributions and your work were not properly appreciated?

Shengelaia: The last one was recently, Neli (Eldar Shengelaia’s second wife) was there as well, I was featured in „Cannes Classics“ for the second time. Neither the Georgian Ministry of Culture nor the government made a single call. Ordinary people meet me in the street, greeting me. One woman hugged me in the street, saying: “Congratulations on being featured in Cannes Classics!” You know, it is strange, but in the Soviet Union, when “Blue Mountains” won the prize in Kyiv, I got a call at 8 am that Eduard Shevardnadze wanted to talk to me. He was the Secretary of the Central Committee then and he said: “Eldar, your achievement is the achievement of Georgian cinema and Georgian culture.” Why have these gestures been lost? Because today, culture in Georgia is not that important. They think about money. I don’t know if I’m right or not. Ha? Am I right? (smiles)

On the reception of his movie “Blue mountains”

One of Shengelaia’s most famous movies is “Blue Mountains” (1984), a scathing satire about an author and the bureaucratic battles he encounters in attempting to get his book published.

One thing I have to say is that when I took “Blue Mountains” I thought that this film is about the Soviet Union and Georgia. I went to India, we showed the film, I was told it was about India. Then we went to Vienna and they told me that this movie is about Vienna. Then when we first showed the film at the Cannes festival, the Cannes festival director told me that if he wrote a letter to the French Ministry of Culture, he would not receive a response either, so this problem [the workings of the bureaucracy are the centre of the movie] exists not only here, but the problem is common, it existed before, it does now, and will do in the future. It is global.

On the Georgian diaspora across Europe

Kheladze: What do you think what will be the future after borders have lost their meaning, and much has become common and many inaccessible things became accessible, will it change attitudes?

Shengelaia:I’ll tell you about that. I am very sorry that almost a million Georgians do not live in Georgia. This is a very big loss. I do not know how, but some means should be created for Georgians to return to Georgia. This is our biggest loss.

Well, I tell you I was in Barcelona, and a Buba Kikabidze (Vakhtang Kikabidze is a famous Georgian artists and singer) concert was held there. There were many Georgians. Plenty. And they all cried as they were watching. Won’t you feel pity for them?

On culture

Kheladze: How do you feel when you sing or listen to a national anthem?

Shengelaia: If anything is rich in Georgian culture, it’s Georgian polyphonic music. I love it very much. Sometimes I sing too, but among family members.

Kheladze: As for the national songs of different European countries, do you know their culture?

Shengelaia: Of course, I do! For example, the Italian song is excellent. Spanish culture, it’s brilliant. The culture of every country is a value. It creates a culture of all mankind, so to say. And I like this or don’t like it, that’s not right.