Vassilis Vassilikos is a Greek writer, TV director and politician, born 1934 in Kavala in northern Greece. During his childhood in Thessaloniki and thanks to a few memorable encounters with modern literature at school, Vassilikos wanted to become a writer from an early age. Nevertheless, due to his fathers’ scepticism he first graduated from law school before moving to the United States to study at the Yale School of Dramatic Arts and the TV Studio School in New York, where he witnessed the invention of video technology in 1959.

After returning to Greece Vassilikos worked as a journalist and wrote his most popular novel Z in 1966, which provided an account of the events surrounding the 1963 assassination of a democratic opposition politician by right-wing extremists in Thessaloniki. After the coup of 1967, the book was banned by the regime and Vassilikos was forced into exile for seven years. He spent the time in France, Italy and Germany, where he was very productive as a writer. Although many stories are written abroad, the characters are always related to Vassilikos’ origin. All in all, he published more than 100 books, spanning both fiction and documentation.

Besides being a successful author, Vassilikos worked as Director of the Greek state television channel (ET1) between 1981 and 1984 and served as Greece’s ambassador to UNESCO. In recent years Vassilikos entered politics, running in the 2014 Greek local elections for the municipality of Athens and being elected MP with SYRIZA in the 2019 Greek legislative election.

In his conversation with Natassa Sideri he talks about his ambivalence towards the EU, having only recently acquired a “European identity”. Vassilikos explains why he was against the Maastricht treaty and very sceptic about the Euro, but glad about the freedom of movement that came with the Schengen agreement. Moreover, he talks about a lecture of Albert Camus 1955 in Athens that changed his perspective on writing, the importance of typography and the future of Greek literature.

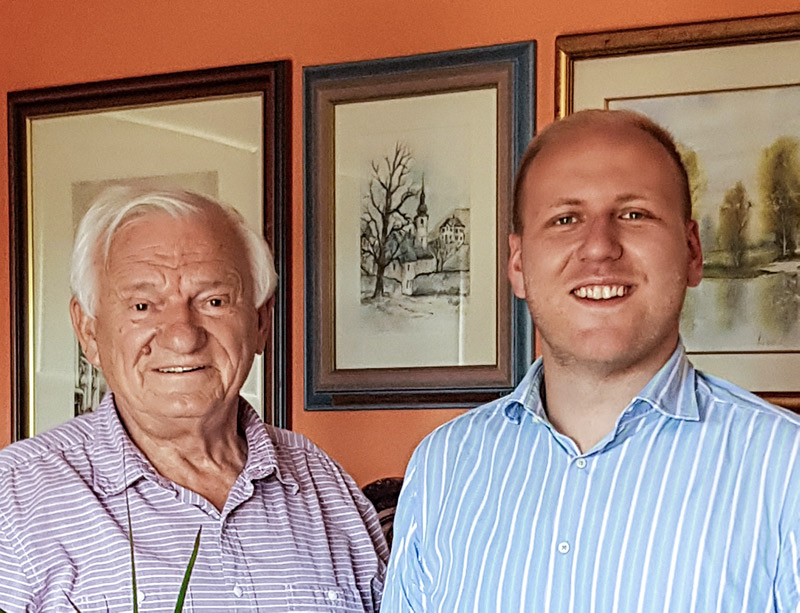

Vassilis Vassilikos was interviewed by Natassa Sideri, who works as a playwright, short-story writer and translator.

Interview Highlights

On cultural awareness

I first went to France in 1955. By then I had already published my first book, Jason, and I went to France to meet Marcel Jouhandeau, the author whose words served as epigraph to that book. But the writer who inspired me more than anyone else was André Gide. Among the Jewish families of Thessaloniki that escaped were the Molchos, who owned the city’s international bookshop.

In 1951, on the day of Gide’s death, I happened to go to the bookshop and Mr. Molcho told me: “You should read this book by André Gide who got the Nobel in 1946”. The book was Theseus, an extraordinary short story that I indeed read and translated — rather badly — into Greek before going on to write my Jason. Gide was an important reference point for that book, as were of course other writers I was reading during that period. I still have some of those books here, in my library, in the old editions I used back then. But Gide, especially, was my god, at least until the day when Albert Camus came to give a lecture at the French School in Athens in 1955, which obviously I attended. There, in the dark amphitheatre, I could see his Algerian eyes looking around the room and I was convinced he was speaking only to me. The room was crammed full of people but I didn’t care. The words of Camus completely changed my point of view. He said that, nowadays, the artist should not be the one stargazing at the prow but the one that paddles. The writer as an engaged subject, that’s what his lecture was about. I tried to meet him during my first visit to France in 1955. I went to his office but he wasn’t there. So French culture served as my introduction and my first bridge to the rest of Europe. And it still does, to a certain extent.

On education

At the end of the year, I had to pass an exam for this class in front of a committee composed of very important people who were there to scout for international talent, as my fellow students came from all over the world. The test was that we had to edit a film on the spot. Each one of us was given a subject and we had 2 hours and 50 minutes to complete the editing and transfer the film to video. Do you know what I was given? The invasion of Normandy. Everything was going very well, I finished editing within two and half hours, chose and transferred my 8-minute long material. Then it was my turn to show my work to the committee.

[…]

It was one of the worst moments of my life. There I am, watching planes reversing instead of taking off and marines sliding backwards! At the end of the eight minutes I hear people applauding. I look around at a loss, “why are they applauding?” I was awarded the first prize among European students. They thought it was a surrealist, Dadaistic approach or something like that and the three major TV networks came to me with blank contracts to sign to take me on as TV director. At that moment, I faced one of the biggest dilemmas of my life. I knew that if I accepted, I would never come back so I started asking myself: “Who am I? What do I want to be? A writer in a country where writers cannot make a living or a TV director in the States?” I was about to sign the contract but then something happened and changed my plans. So I came back to Greece, where television hadn’t even arrived yet.

On work

Yes, exactly! But the place where I wrote the most books was West Berlin. I wrote 14 books in 12 months! I was there on a DAΑD scholarship [German Academic Exchange Service]. Back then, Berlin was a zombie city and they wanted to have some foreigners around. That was in 1969-70. By then Z had come out so they gave me and many other people scholarships to go and live in Berlin with the sole obligation to walk up and down Kurfürstendamm for two hours a day. The reason, you understand, was for everyone to see that there were people from other countries present in the city.

Anyway, something happened to me while I was in Berlin. At the time I would only travel by train. A plane I had been on a few years before had split in half during landing and even though there were no casualties I didn’t want to fly anymore. So I would take the train into the West Berlin station and the moment I arrived there, I don’t know if it was the climate or the fact that I didn’t speak a word of German, something would happen to my brain. I had this tremendous desire to write, which translated into an important production of books. Unlike France, where I never wrote anything, my inexistent German prevented me from participating in any other form of social life.

On the state of Europe

To tell the truth, though, I am deeply saddened and disappointed with the present state of Europe. I never thought we would get to the point of forgetting that migrants helped shape Europe as we know it. People who left their countries in the past were welcomed in various European cities, especially in Paris, and greatly enriched the culture of the receiving countries. People like Picasso, Costa-Gavras and other great artists, France took them in its arms and they became part of it. All of this is finished now, from the moment we entered the reign of money. For my part, I have understood that money exists in its own right. It doesn’t need any products. Money is “plastic” in the sense that it exists for and by itself. “Art for art’s sake” we used to say back in the day, which was a bad thing for art. Nowadays we could say the same about money. “Money for money’s sake.” That is the end of the road and of human existence. If money is God, without a base, without even a church to be worshipped in except for banks and the exchange market, then this is not a good place to be. This is where Europe is right now and Greece had to pay a high price for this as it was given the wrong medicine.