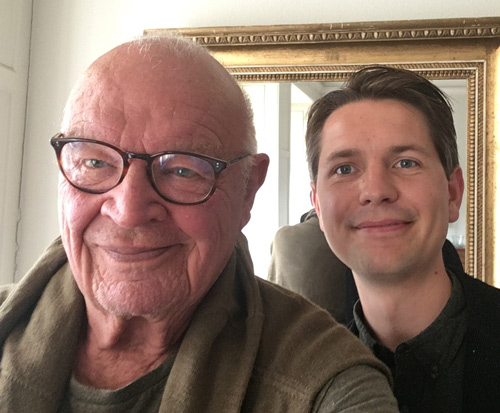

Interview by Markus Floris Christensen

Denmark, August 2019

Christensen: As you know, there are a great number of topics for us to cover, as I wrote in my e-mail to you, and I think I will list them again just to refresh our memories and so you have a broad idea of what this is all about, and the first topic is home and childhood. The second, education or general education in a broader sense, as I have chosen to call it. The third is work, the fourth political awareness, and after that, the fifth, which is cultural awareness with freedom being the sixth. And then we’ll glance towards the future, or, as I call it ‘look into the future’. Then we move on to conflict and resistance, religion being the second to last, and finally, Europe in 50 years.

Barfoed: Yes.

Christensen: And that concludes the list of topics we are to touch upon and now we can go through them. And we can go through them, more or less, thoroughly or superficially depending on what we find interesting to delve into. And now I’ll just make sure that the sound is coming through here, and it seems like it is.

Barfoed: So it seems.

Christensen: It is. Wonderful. Then everything should be working.

Barfoed: Splendid.

Christensen: Yes, and before we begin, I would like to introduce us both. My name is Markus Floris Christensen and I am a PhD student in Literature at Europa- Universität Flensburg. I am visiting the private home of Niels Barfoed, who, as you know, is a writer and literary critic. He has contributed to the Danish literary scene as a critic, journalist, newspaper and journal editor, as a lecturer and researcher, and as president of Danish PEN. Furthermore, he’s been an important advocate for persecuted writers and dissidents from Eastern Europe.

Well, I will start by asking you about your childhood and youth, and about your professional life. After that we can continue on to the more complex topics such as political awareness, freedom and religion.

Barfoed: Yes.

Christensen: To briefly note for the uninitiated – where did you grow up? And what thoughts do you connect with your childhood home, if we are to create a general picture?

Barfoed: Yes, well, I also find it very important to begin right here, because if you are European in one sense or the other – not in a highbrow way or anything like that – but in a plain geographical, cultural way, then it has to bloody start somewhere. That place will of course be, amongst others, my childhood home.

Christensen: Yes.

Barfoed: I am a Copenhagener at heart. I come from a middle-class background. Not high society, not low – but somewhere in between. My roots are connected to doctors, priests, and partly writers and higher officials on my mother’s side. One could call it a cultural home or a home full of culture without it being emphasized in any way. When I think about it, no one seemed to be aware of the culture they possessed or conveyed, but nevertheless, that’s how it was.

I was born in the 30s, and I understood the depression as endless rows of unemployed workers standing in line in front of job centres. I can still see them standing there. I couldn’t understand why so relatively many people were standing in such an orderly way along the sidewalk of a street in Copenhagen called Kattesundet.

I am a child of war. I was 9 when the Germans came and 14 when they left. Then we knew that there was something called Europe, but only as it existed in in my father’s old illustrated books, in which you could see Florence, which at that time was a place that found itself in great chaos, and which was a smouldering ruin all throughout the war.

And that extreme isolation, was broken in ’45. But, of course, it wasn’t replaced by an actual opening, a dynamic opening towards greater Europe, because all around us there were only ruins. And there was no denying it, really. And if you tried to anyway, you had to be older and more daring, or you had to move past it and on to something which looked like a Europe – if that’s what you wanted.

Europe to us was something unknown, and that is often difficult for young people to understand. Europe did not exist in my childhood. Only figuratively speaking in writing and in badly-printed photographs and badly-printed books.

Christensen: (laughs) Yes.

Barfoed: That was Europe. That was it.

I discovered Europe indirectly, because I was lucky enough, as a very young man, to be granted a trip, and that trip was arranged for Greece. And back then you reached Greece with a rumbling, labouring train through Europe – it took four, five days to reach

it. Through a Germany where beggar’s children were still standing on the platforms begging for money.

Down there, the only way that I could return home after several months was to take a cargo ship that docked in Smyrna or Izmir.

The Germans called it Smyrna, and we called it Smyrna, because the Germans did. They had hardly ever seen a young European man in Smyrna or Izmir before, and I myself had never seen anything like it. What filled me with anxiety was that I found myself in a boiling, boiling street with poor and more or less invalid beggars, who lay on pieces of wood with wheels underneath, and the elderly who smoked waterpipes. And then there was this old man, sitting in a tower yelling and screaming from the top of his lungs, whom they called a muezzin?

And right then I felt like this under-educated European, who was far away from home and who all of a sudden found himself in non-European circumstances, in this culture, the Turkish one, you know? Where I didn’t belong.

It was a nightmare like you cannot even imagine but you repeatedly find young people who say: Why on earth didn’t you enjoy it?

Christensen: Yes.

Barfoed: Because first of all, there was this complete sense of alienation a sort of stuffiness in a Europe that was burning, and in which the fire had only just been put out.

Christensen: Yes.

Barfoed: It is a condition which is completely obvious to me, and it belongs here and will always serve as a background. A sounding board, if you will – no, actually, an underlying tune for my relationship with the world around me, and, in this case, for my relationship with Europe.

Of course, I arrived later to Europe, because we were part of that generation that only used its thumbs, you know? Travelled by thumb – you wouldn’t say that today – hijack

– what’s the word again?

Christensen: Hitchhiking.

Barfoed: Hitchhiking, of course! Yes, that’s it.

Barfoed: I attended a very old-fashioned school, an all-boys primary school and all- boys secondary school. Very old-fashioned teachers with starched collars and lorgnettes, who, when it came down to it, were very aware of their own classical education and they wanted to pass it on to us. It wasn’t always smooth sailing, as you can read in Klaus Rifbjerg’s Den kroniske uskyld [famous Danish novel on secondary

school-life, Terminal Innocence tr., written by Klaus Rifbjerg, one of Denmark’s greatest writers, who was Barfoed’s friend growing up]. He actually attended the school I am referring to. Klaus was in the grade below me.

And with that in mind, now that we’ve entered secondary school life, we’ve also entered the post-war period, in which it is evident that the language classes especially introduced us to a kind of literature which we began to sense. On the one hand, it was not our own, but on the other, it was based on some well-known elements that were not as distant or alien to us as one might think.

Thomas Mann was probably the most modern writer we were introduced to. And in Denmark, in Danish classes it was Johannes V. Jensen [Danish writer and Nobel Prize winner from the early 20th century], who was the most recent.

Christensen: He was the most modern writer?

Barfoed: Yes, he was the most modern writer we read back then. But, in Johannes V.’s writing there was something, if it wasn’t European in the general sense, then it at least had some Nordic traits, and in Herman Bang [famous Danish writer, b. 1857] one could sense this Europe like one could in the writings of Henrik Pontoppidan [Danish writer and Nobel Prize winner, b. 1857].

Christensen: You got it through literature then, more or less?

Barfoed: Yes, I’d say so. With films – no. There were no limits to how American they needed to be right after the war.

Christensen: True.

Barfoed: And the Americans were our heroes – especially because they introduced us to these wonderful Lucky Strikes and Camel cigarettes, and then we were the ones begging, you know? (laughs)

Christensen: Sure.

Barfoed: The Americans were the ones who really counted, you know? German literature, in contrast, that was only in school, right?

Christensen: Yes, yes. Marvellous. Let’s talk about the time during the war a bit. In your memoirs you described the commotions that took place by the Great Synagogue in Copenhagen in 1943, and how one should stay away from the windows.

Barfoed: Yes, yes.

Christensen: Other than that, you were in Dragør [city on Amager near Copenhagen] with Jesper Jensen [writer and musician, and Barfoed’s childhood friend] when the nuclear bombs were dropped.

Barfoed: Yes.

Christensen: How was that time period, and being locked up?

Barfoed: Well, in my family you followed the mainstream, in other words, tendencies or general ideas held by the public, which was to surrender completely, to close your eyes and expect it all to pass. That was my father’s attitude. I won’t hold him accountable for it today. Our house was actually on the corner of Ny Kongensgade and Vester Voldgade, with a clear vision of the Great Synagogue, and there was also a Jewish building there, with private homes and meeting rooms.

And then they came in October 1943 and it is thought-provoking to see yourself standing with your father and looking down and watching that street, knowing that we see it, but don’t really see it, you know? That was our general attitude.

And well, yes, there were guards, and there were people who were nationally and ethically as well as morally and politically aware. My father was not one of those people. He was a dreamer and had a sort of artistic nature. He didn’t really need anything other than his drawings, pencils, some cigarettes and his leather armchair. That was all he required to feel comfortable.

So, yes. That’s how it was.

Christensen: Yes.

Barfoed: But that was the general backdrop. We listened to English BBC broadcasts with the help of a jamming station – wau, wau, wau [sounds imitating the radio]. We pretended the Germans weren’t there. When they entered a tram, we would move to the opposite end of it, because the presence of a German soldier could easily create some chaos. That’s how it was.

Christensen: That’s exactly the kind of details my generation can benefit from hearing, as we have no recollection of these things.

Barfoed: Well, that’s good then, yes.

Christensen: Yes, if we can return to the subject of belonging.

Barfoed: Yes.

Christensen: To which place do you feel the strongest sense of belonging? And how has that feeling changed throughout your life?

Barfoed: Yes, that’s a big question. Well, curiously enough I actually found myself having a greater sense of belonging to – funny as it might sound – the turn of the century. And that is because my grandfather was a rather prominent doctor in

Svendborg, a large market town, and that culture, which my father boasted of uncritically, that is also my culture.

My friends lived in the times of Poul Henningsen, [who was advocating cultural radicalism in Denmark as well as preaching modernity and the liberation of minds] because their parents were modern, and knew how to act according to Poul Henningsen and how to be a little radical à la the 1930s. And perhaps they flirted a little with communism when the times were right, but that was not in any way the case in my childhood home.

My childhood home was paintings by Fritz Syberg, an orchard, sounds of an apple falling to the ground – a quiet, fine provincial town. That was my father’s world and it was completely unaffected. He once fantasied about returning to Svendborg and building a little house by Svendborgsund and watching the ships pass by it, and writing about it in his journal or something like that. That’s how I imagined it, but that didn’t quite suit my mother. She was unmistakably a Copenhagener and came from a family of officials. Her father was a historian.

But, home, I definitely connect the idea of home to a certain kind of Danishness, but not in any nationalist sort of way. We attended community singing in Dyrehaven, and we were so happy when the Dannebrog was raised all the way to the top and encircled the tower of Christiansborg, and so forth, and the king, you’d have to admit, his presence was strongly felt throughout this time. He was the rallying point, but we were only 11 years-old, so we didn’t know what that was (laughs), you know?

But he was there, and he was somebody very important, and he had to be defended when he came riding through town on his horse, which he always did on Sundays at least, and perhaps even more frequently. When he came riding like that, he was defended by the Danes, and it was like an incredibly idealistic little painting of a safe area in a devastated Europe. We were safe.

My home, figuratively speaking, was a safe place. Denmark was safe, we were safe, we were protected by the power of Danish politics. Of course, we didn’t know whether it was good or bad, and my father had no opinion regarding Scavenius’ [Danish Prime Minister 1942-1943] politics. We were protected to a certain degree from Werner Best

– and perhaps, even from Berlin, right?

Christensen: Yes.

Barfoed: So, it’s funny, really, this is coming to me as we’re speaking, this security during a complete Armageddon, which was happening to the rest of the world, you know? We could hear evidence of this on the radio. The news were subject to censorship by the Germans, naturally enough, given all the stories of pullbacks and bombings being depicted, and we ourselves were submitted to air-raid warnings and had to move to the basement once a month or about that often.

So that is characteristic of the Danish condition, and I dare say that that security is still maintained in our national character. To some extent, we are oversensitive and very afraid of risking our own skin, you know?

And especially when it comes to our kids, right? Kids are not allowed to do anything these days because of the helicopter watching from above. All that, I think, is a product of our caution. It is the caution of the spoiled. We are used to everything working out, if you don’t take too many chances and that kind of thing.

It’s still there, it’s still there.

Christensen: In the culture and mentality?

Barfoed: Yes, and also somewhere in our political awareness, I think. Somehow, but that’s the kind of thing which is difficult to determine.

Christensen: Yes.

Barfoed: But my youth was in the post-war period. For people like me, who wanted to be poets and wanted to be something, that involved music, perhaps, or wanted to be a little bit intellectual. For us, on the one hand, one could continue the communist tradition from the war, and there were clear traces of communism in the resistance during the German occupation, you know?

It also led to a short communist period in post-war Denmark, but that wasn’t for me. I found myself with a greater sense of belonging to an anti-ism-movement. Meaning that all -isms have shown how utterly useless and destructive they are, whether it’s fascism or communism. Art was the only reliable and uncontaminated thing left, right?

Christensen: Yes.

Barfoed: Art, the free thing, the free, cultural expressions coming from poetry etc. That was the future, and that was ‘gefundenes fressen’, when that was actually what you really wanted. (laughs)

Christensen: Yes, yes, yes. (laughs)

Barfoed: Already, and that also lead one away from what you call political awareness. I wasn’t actually politically aware until very late. And the interesting thing is that it didn’t even happen in October 1956.

Christensen: Was that a turning point?

Barfoed: It could have been, but it wasn’t. It probably was for a lot of other people. However, many people in my circle, the people I socialised with and liked to socialise with, for them their turning point wasn’t Hungary. Actually, and frankly put, I am pretty embarrassed about my own past. (laughs)

The turning point, due to different meetings and situations, would be 1968. It was that late.

Christensen: Alright, I see.

Barfoed: And by then I was 37 or something, wasn’t I?

Christensen: Yes.

Barfoed: Yes, it was late, and then there was everything up through the 60s, the Dubcek experiment especially, the cultural blooming, right?

Christensen: Yes.

Barfoed: Well, the Prague Spring with Milos Forman, with Milan Kundera, with the whole group of filmmakers and graphic designers, who were cheeky devils in all sorts of ways.

Christensen: (laughs)

Barfoed: Yes, that’s when I woke up, and that was because it became my, how should I put it – destiny is such a fancy word – but in any case, it became my, fascination and my focus point. Yes, the work of dissidents in Prague and then I expanded to Hungary and to Poland, and wherever else I might find myself, and in the end Romania as well.

Yes, well, right there, that’s how late it was, and that’s exactly when Europe functioned not only as the Western Europe we knew, which in the coldest of wars, which was the beginning of the 50s – that was the first Cold War, wasn’t it? During that time the West was challenged and let itself be challenged to demonstrate its values quite considerably, not just through NATO, but also through rhetorical means.

Christensen: Yes. Maybe it would be interesting to talk about your transition from being apolitical to political. You’re moving in the milieu surrounding Heretica [Danish cultural conservative journal, which played an important role in the ‘50’s].

Barfoed: Yes.

Christensen: And also, the publishing house Wivel.

Barfoed: Yes.

Christensen: And you are actually very present in this milieu.

Barfoed: Yes, and we were actually very caught up in the past, you know Hellas and those, greater European cultural movements that were a little classier, they were present in Heretica. But I think, I can almost identify the change, it obviously gets complicated by the fact that you start travelling for real, but then your travels become

less and less frequent, you know? Sea bathing, coconut milk and straw hats and much more. Cultural journeys, political journeys, you know?

And the first trip to Berlin, that was in ‘58, It was a trip arranged by, I was just about to call it the “West German Ministry of Upbringing”, but nothing was called such a thing, and there wasn’t a Ministry of Propaganda either. But there certainly was some sort of department in the Ministry of Home Affairs in Bonn, which had come up with the idea that they needed these trips to show off the new Germany, so people could see how much its democracy had developed etc., and rightly so, because they had come an incredibly long way.

Christensen: In 1958?

Barfoed: Already by then, yes! Very well done, they had every reason to be proud of that, and to show it off, but naturally, well, we were wretched young journalists and, well, we could easily understand how they wanted to sell their – how do you put it – show off how nicely dressed they had become since the old days. And they were completely entitled to it.

On that occasion, we arrived on a bus, arranged by a department in the Ministry of Home Affairs, and it took us from happy glowing Berlin, West Berlin, with loud music playing on the radio and pop music and so on and then on to the gloomy, dark, obscure, empty, poor place which was the DDR.

Because there was no wall.

Christensen: At that time.

Barfoed: At that time, no. It only went up in ’61, and by then we were tossed out and shown Karl Marx Buchhandlung, where you can only find one book with 3 million copies, and that was Das Kapital. And then you find three miserable Mütter knitting while serving us, and we saw those banners above the stores saying: ‘Wir werden nie den Sozialismus aufgeben, Der Sozialismus hat uns gerettet und so weiter,’. And then we came back, and we crossed the border – there was no wall – and then Mrs. Minister of Home Affairs was showing off, standing there dancing and prancing, celebrating that now we were back in the West again.

But that’s how it was. It didn’t continue to be like this. But that’s how it was at that time.

And then the Wall came, and the experience I always connect with the Wall, with the DDR was when I tried telling myself that I had made plans with Wolfgang Biermann. And I had, but exactly when and at what time, either I had or I hadn’t made a note of it, or I had misplaced it.

And I arrive in East Berlin – Chauseestrasse – I think it was, but I do not call him on the telephone. I could have actually called him from a phonebooth telling him I was on

my way – but I just walked up to number 112 – he was on the 3rd floor – and rang the bell. But there was no answer. Well, that’s too bad, and then I tried the bell one more time. And then, all of a sudden, the door is swung open and there was Wolf right there, and he said: ‘What in God’s name are you thinking? What the hell are you thinking? If you call on me unannounced, then I won’t know it’s you, and then I’m sure it’s the police. At this time he was wanted and pursued wherever he went.

So, he actually told me off in a way I’d never experienced before not since school in any case. And I apologised. And he said: ‘Let that be a lesson. If you want to stick around here, where you are now – and you’re welcome to – we might actually be able to make use of you. But you need to wake up. You need to realise where you are.’

And then he let me in. He showed me mercy and let me in, and then we sat there all night. And there was this British hippie – I know exactly when this was because of this hippie who had just heard the newly-released Beatles-song ‘Blackbird’ and told us to listen to it, then he sang it to us.

And this union of Biermann and Blackbird and a British hippie. At this moment, something was about to happen, because it was all weighed down by this burden and by this dividing line. This line about which I had just been told off for not taking it seriously. From then on, I took it seriously. And that is because of Biermann.

Through this chance meeting, or coalition, he also contributed in making me aware of Europe as an actual reality, connected by blood, and that must have been around the time of ‘Blackbird’. I think around ‘73.

And this was when everything got started, and I found more writers from East Germany, and then I have to say that it is better or more tempting to be a journalist or a reporter in a totalitarian regime, because you’re sort of welcome. You don’t have to drag it out of people. They are ready to tell you the whole story in the hope that I’ll make the story my own – that I’ll take it, swallow it and bring it back to the West to throw back up again, right? That I would take advantage of it, because they really needed the exposure.

And that is, of course a luxury. I’ve worked as a journalist in other places, where people would just say: What’s in it for me? You know, as if I were to get something out of them, right? (laughs) That’s not exactly what they said in East Berlin or Prague: What’s in it for me? No, they were happy to tell you everything! And that was in many ways extremely important, as the more the West was aware of their situation, the more it was ready to give in terms of defence forces.

I may have been a writer, who, back home not only had issues with reducing his taxes, or had to discuss if the new cost-of-living adjustments were good enough, but for Biermann it meant life or death if he could sing a certain lyric with a particular word in it, or if he better remove this word or replace it with something else. Everyone

considered these things, and if they then chose to say fuck you to the system, that’s something else. But they all started out by considering this: Should I be stubborn and what price would I have to pay if I were? Would it be worth it? If I sell out just a little bit, then would there be any issue at all?

And it was right across the Baltic Sea, you know! Right across it. You could reach the place in no time. And you were on foreign grounds, while still on European grounds, and there were those people whose lives were determined by a rebellious day-to-day existence. You could see all the people who had just given up and come to terms with it, and of course that was the vast majority. Most people didn’t like it, but they could return to their cosy datchas, as their summerhouses were called, which they had built themselves. Here, they could grill carp and perch, caught in a lake nearby, and then they would sit there discussing the new Trabant – when they’d get it and how they’d been allowed to buy one. And that too was a way of living! Let’s not be narrow-minded. That was also how life was lived. By many people. It was a way of surviving.

Christensen: Now we have delved deep into your travels during the 70s and the 80s.

Barfoed: Yes (laughs).

Christensen: And your orientation towards Eastern Europe. But if we can take a step backwards.

Barfoed: Yes, fine, you should do whatever you feel like.

Christensen: I know you also went to the United States and stayed at Princeton.

Barfoed: Yes, right you are.

Christensen: And I’ve read that you’ve even shared a table with Thomas Mann’s daughter.

Barfoed: Yes, yes, I did. Her name was Elizabeth.

Christensen: …and that was towards the end of the 50s?

Barfoed: Yes, Thomas Mann had passed away four years prior to this meeting – that sounds about right.

Christensen: And now onto the 60s and ‘68, which you have defined as a sort of turning point in your political thinking.

Barfoed: Yes, it happened before ‘68, but anyway, you’re right, if we must identify a particular point in time in such a way, because it was also – roughly speaking – the end of hope. One just didn’t think time could be reversed, but the Communists were bloody good at that – I will grant them this much. And if I am to say something that they were good at, the Communists, it would have to have been their ability to cut the

head off a snake and make it clean windows! (laughs) That was a silly way of putting it.

Christensen: (laughs) No, no, it worked! But during the 60s, you were also involved in Vindrosen [a significant Danish literary journal, published in the period 1954-1975] and deeply engaged in the literary scene of the 60s back home in Denmark. What were your passions during this time, in terms of literature and aestheticism? I think we ought to include that too.

Barfoed: Oh, yes, I think you’re right. Well, I made a marvellous discovery – if you allow me to use such a phrase – through Villy Sørensen’s [leading Danish modernist of the 60s] way of understanding literature in Digtere & Dæmoner’ and his interpretations of folksongs etc. This way of understanding literature based on psychology- and philosophy, as opposed to nationalist beliefs, as Vilhelm Andersen [Danish literary historian from the early 20th century] did.

To me, that was a great breakthrough, and I am deeply thankful for that experience. It must have been around ‘60, ‘58, ‘59, ‘60. It was an incredible push and I also realised that Villy didn’t invest all this time in folksongs and the like. He also had opinions on the welfare state and on ideologies and that kind of thing, and early Marxism – so he was not narrow-minded in any way. This was probably my real education, if you will. Villy Sørensen and modern literature educated me.

So you can go ahead and call Thomas Mann old-fashioned or an obsolete writer, but Vindrosen was also a mouthpiece for modern European literature. And for this reason, people like Enzensberger and Grass, naturally, stood at the front line whenever we had to make references to European literature.

We also published a special edition about Yugoslavia, –Tito’s Yugoslavia – the country’s literature, so when editing that number, it was my duty to provide our readers with information about the state of Europe.

And that duty did not continue into the time when Ejvind Larsen and Jørgen Bonde Jensen were editors [editors at Vindrosen after Barfoed]. Their periodical was about political liberations, revolt and so on – everything Joschka Fischer represented.

Christensen: So, in terms of your work, there’s already at this point a focus towards Europe, and in fact, Eastern Europe?

Barfoed: Yes, you can definitely say that. That’s right. There were Eastern writers who took me in as a literary critic, naturally. I do actually have a volume from ‘67-‘68 called Ajourføringer [Updates], which is a collection of 20-25 literary reviews, contemporary reviews, and in it you will find Max Frisch, Günther Grass, and Enzensberger. Obviously, Rifbjerg is there too – he was part of that group – but I also think that I would call myself a cultural radical. Not by nature, but as someone who shaped opinions, I was part of that wing for a number of years. But the thing that made me

stand out and made me not see eye-to-eye with them was the complete pacifism that they were determined to keep during the Balkan Wars – but now we’ve moved all the way to the, is it, the 90s?

Christensen: Yes

Barfoed: But (laughs) there are a lot of years in between, but during those years, I think you can identify my move away from the, let’s say knee-jerk pacifism, which led me to no longer belonging to that political wing. That was the reason why, along with the aftermath of the Wall coming down in 1989.

In ’89, the best thing would have been a sort of capitalism with a human face instead of a socialism with a human face.

I found it to be completely straight-forward, but, well, there were a lot of people on the left who said, no, now we have the chance to go down the third road. Which one? I’ve never heard of this. But they believed there was a third road in which you couldn’t find either of the two. They were so smart about acting on behalf of other people, weren’t they?

Regarding the East Germans, they thought that Round Table should revolve around a sort of improvement of their socialist model, which had stagnated, right? On the basis of liberation, it could be woken once again as a prosperous (..) model.

In the meantime, my best friends in Eastern Europe – who knew better than everyone back home – said: Excuse me, we’ve had enough, and we’ve been fooled enough times with dreams about reforms making everything right again. Then they said: We will echo the words of Konrad Adenauer: Keine Experimente! (laughs)

We won’t do this anymore! Enough was enough. We’ve been obedient since 1945. ‘Can we please be left alone? We want lives just like yours! And that’s it!’, ‘What? Like us?’ ‘We’re in a terrible state! We’re suppressed by capitalism!’ [Barfoed is imitating a dialogue between East and West.] But we just want a tiny little refrigerator? What, are you materialists?! (laughs) Is that it? I actually thought we had moved passed that.

And I had moved in these circles for so long, interacting with such intelligent minds who took their own experiences into consideration, but didn’t ask themselves if they knew how that person on the right or on the left felt. Here in the West, we sure knew what was best. ‘By no means should you reunite with West Germany.’

No, now you have the opportunity to create your own confederacy. What kind of foreign politics would you have, I asked, as did others. Well, that would be sorted out somehow. I’m sorry, it cannot be done. You can dream, but do not dream on behalf of other people, because you’re not the one paying the price, goddammit! You’re sitting here, no troubles at all, in your ivory tower.

Christensen: Yes, that is really ridiculous, I’d say.

Barfoed: Yes, well, that’s how it was back then. Havel was great, simply fantastic. There was all this talk about the peace movements. That was where there was a really significant action. Saying no to atomic weapons, we can probably all agree on that being a good idea, but the peace movements, this idea of turning swords into ploughshares, that kind of thing, you know?

And unfortunately, the peace movement was infiltrated by communism a great deal, but when I had the chance, I talked to Havel about these campaigns and the travels of these pro-peace individuals.

Christensen: This is a conversation with Havel?

Barfoed: Then he said: You tell me – what do you need peace for in prison? But it never really occurred to us that they were imprisoned. We were also imprisoned, they said, right? Imprisoned by capitalism. But I mean: Come on!

And one thing that was characteristic of the time was so-called egalitarianism – no one is better than anybody else. Forget about everything else, it’s not about who’s right and who’s wrong in the West. It’s about having a shared ground to stand on, which we all feel equally bound to. This is more liberating then the one that is forced upon you. Can’t we just start there? Can’t we just agree on this?

Christensen: That, then, is your meeting with Václav Havel. And you do make a lot of trips to eastern European countries during the 80s and you also met Hertha Müller and Wolfgang Biermann, as you told us before, and that is very much what you describe in Hotel Donau, which was published in 1989 and reprinted in 2017.

Barfoed: Yes, that’s right, Floris.

Christensen: Yes. (laughs)

I, of course, at this time was also in close contact – and still am – with a great editor who had a grand view of the world, and that is Herbert Pundik. He supported me and inspired me to ‘go for it’ in Eastern Europe. Do whatever you want, do it fast, do it often, do it many times. Your newspaper has got your back.

Christensen: That’s marvellous.

Barfoed: Yes, he was very fine and he was actually of Russian descent. His grandfather or great grandfather was born in Kiev, so he had this Russian connection to the Soviet world. So, without Politiken [Danish newspaper, which Barfoed worked for in the 80s. Politiken supported his trips to Eastern Europe]. I wouldn’t have been able to do it, wouldn’t have travelled like I did, on-and-off, sort of and back-and-forth, and wouldn’t have been able to make books out of my observations. No, I have

Politiken to thank for serving as a platform, without there being any restrictions of any kind. I kept having that job at my disposal.

I don’t know if that was enough? (laughs)

Christensen: Indeed, indeed, it’s very good.

Christensen: We are moving towards a crucial event. In 1986 you were present at the ceremony in Prague when Politiken and Dagens Nyheter conferred the Freedom Prize to Havel. We don’t have time to go through the entire story, but can you briefly outline what was really going on?

Barfoed: Yes (laughs), I think I can give a brief summary. Politiken and Dagens Nyheter had established this Freedom Prize, which was to be awarded to people from all over the world, from South Africa or anywhere, who had sacrificed themselves and spent all their energy focus on the liberal ideas of freedom.

In other words, human rights, democracy and so on. It was Havel’s turn to receive it, and because of my connections it was completely natural that I should be the one to present it to him. And then in Stockholm, there was, briefly put, this very important leader of something called the Charta 77 Foundation. Stockholm is where Charta 77’s headquarters is located in the West.

He was sent to brief me, because I needed to learn how to become a secret agent. (laughs) And now, in retrospect, I know that he was aware of the fact that I was going to get caught, but he was just sitting there playing his part (laughs). It had something to do with never carrying phone numbers on me. I needed to memorise them by heart. Well, anyway, away I went.

And I rented a video camera the size of a sewing machine, but believe it or not, I was able to bring it in, and now I have this suspicion that they let me bring it in to make sure that I had at least done one thing wrong. Because it’s better to have some evidence if you are to claim that this man is up to no good, isn’t it?

Christensen: Yes, yes, of course. (laughs)

Barfoed: So I get in, and a meeting is set up very fast, and you know, when these people are to meet, it’s better that they meet each other straight away, you know. So they would say get here in 20 minutes instead of at 10 pm, because then they would have given the enemy some time. That’s what it was like there.

And then the old man showed up, Dubček’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jiří Hájek. And of course, that was a fantastic event. I couldn’t bring the prize money, obviously, but I could bring proof that it was in a particular bank account in the West, and he thanked Havel and passed on the word to Jiří Hájek, who in turn thanked him. The next day I wanted to interview Havel, and was allowed to do that, but he told me that I should

probably hurry up and leave. (laughs) And as it turned out, they were right. I was caught in my hotel after having visited Jiří Hájek. I wanted to interview him, you know, just like I had interviewed Havel. He was a very important man, really, he was. He was the one who demanded at the Security Council that the Russians leave Prague around 21 August 1968, and who, unlike all other grand, fine Czechs in exile – or Czechs, who just happened to be out of the country – went back home. He left the next day and stepped out of the plane like this. [Barfoed gesticulates, puts his arms up in the air like a man who has surrendered]

Christensen: Even that is a crazy story.

Barfoed: Yes, it is. I wasn’t convicted of anything, and they wouldn’t have gotten away with it if I had been, because Czechoslovakia was part of The Helsinki Accords, which were brilliant, so nothing happened. In the old days one could have wound up in the Moldau, or whatever it’s called, Vltava [Czech word for the river Moldau] but not in ‘86, no, no.

Christensen: So, you came back home safe and sound?

Barfoed: Yes, yes, absolutely, absolutely. But I was humiliated on the way back. They couldn’t help themselves, of course, now they had their chance. This was at the border crossing to Germany near Bayreuth, the outermost tip of Czechoslovakia, which extrudes into West Germany. There was a table, which wasn’t any broader than this, [Barfoed gesticulates: shows a width of about half a meter] but it was, however, 12 metres long. On this, you had to present all your possessions with five centimetres between every item. Every little thing you had, and then your body was searched. Thoroughly. It was humiliating.

But I was not in any danger – besides that of experiencing the agonies of having to prepare for questioning. How do you prepare yourself to be questioned? I can say this, because they know this already, and that thing they can probably guess, but I better not say that, and what if they ask me, and then it’s a complete mess already, isn’t it? Well, nothing happened, so there was no problem.

Christensen: Which was a good thing, yes. Now let’s turn to the subject of all your travels.

Barfoed: Yes, we forgot about the United States, but maybe that doesn’t matter. Maybe.

Christensen: Yes, let’s just stay on this track. If you look at it a certain way, you can regard your many trips and countless meetings with Eastern European intellectuals as an attempt to connect the cultural with the political.

Barfoed: Oh, well, okay.

Christensen: How do you understand the relationship between those two things – between culture and politics? And what is it that primarily unites Europe – is it culture or is it the collaboration between finance and government – both then and now?

Barfoed: Well, what was characteristic of totalitarianism was that there was not a single area of society as whole which hadn’t been subject to a political function, and therefore, culture and politics were one and the same thing within their scheme of things. And that’s exactly what made it problematic to many artists, who weren’t inspired by the fact that everything they did had to fit within this political-cultural institution, that had been determined by the party. And for this reason, they started doing whatever they wanted, but that turned out to be completely impossible.

That was even the case in Hungary, where things were loosening up a bit, but still under constraints. You shouldn’t overestimate Kader’s liberation process. As has always been said: Hungary was the happiest hut in the camp! The country was a hut (laughs).

Christensen: But at least it was happy, right?

Barfoed: That is actually kind of true. But well, it has something to do with individualism. Individualism was set aside as, shall we say, a sacrosanct term. We’re talking human rights based on the inviolable individual and their rights. And that’s the counterpart to collectivism.

Yes, and therefore, contact with the West was so important, and I was one of the people who could act as a conduit for that contact. It was important for them to gain access to Western literature and we smuggled that in. And it was important to them that their manuscripts could find their way going in the opposite direction, to the West, to those journals, which had been established over there, journals which focused on Eastern European literature.

But Europe one was part of, a small part of a grand machinery – to put it quite simply

– which wanted to recreate liberal circumstances within itself. One which once had liberal circumstances, but of course, as an Empire.

But yes, you dreamed of being able to contribute to this development, and that it would have some effect on whatever risk was connected to it, such as instabilities and prosecutions, as in Berlin during the last days of the Cold War. It was supposed to be a gradual progress, […] but it then happened so fast. But yes, that was the dream, right? That was the intention.

What we didn’t know was that one day in 2019 you would realise how little liberalism actually had taken root. So little. In Eastern Europe, liberalism is almost as present as corruption, and it evolves into corruption under the circumstances in Eastern European today.

You wanted liberalism to be established on its own terms, and it did for a long period of time. That’s exactly what’s at stake today, isn’t it? Those roots have turned out to not be deep enough. In Hungary, in Austria, in Poland. Austria is part of this now. You find a strange sort of melancholy connected to the exact thing we were fighting for, and which we were successful with, thanks to Gorbachev, thanks to many factors. It was instituted where it rightly belonged – because now, what belongs together, grows together and as Willy Brandt said by Brandenburg Gate – that is exactly what’s at stake right now. That’s the exact project, which is at stake now.

Christensen: You mean integration?

Barfoed: Integration based on the EU’s conditions. That’s what’s at stake now.

Christensen: Do you think it has been taken too far with respect to finance and government, and that the meaning and importance of the cultural has been forgotten in the process?

Barfoed: Yes, I do. In fact, I think it has been underestimated. –That is, cultivating beliefs that would make people see what was truly beneficial, luxuriant and liberating, how we could benefit from a state governed by law and that we can benefit from defeating corruption.

There’s no way that a person could bribe a doctor here in Denmark, and if they could, the doctor would most certainly suffer the consequences on the front page of Ekstra Bladet, right? There’s no way it could happen, and many foreigners cannot comprehend this fact.

I can only see how the EU easily can seem monstrous to the average person who, on the other hand, knows the national costumes, the national music, the national dance, how to throw a party, a speech from the heart about me and my past, my ancestors and my history.

Or about the time we fought against the Turks by the walls of Vienna – now they’re there again, so we know what to do. We need to keep them out. [Barfoed is imitating the nationalistic, xenophobic way of thinking.]

Christensen: Yes, we briefly touched on the matter of freedom and that of free movement and borders. Has the abolishment of borders in Europe been important to you?

Barfoed: Well, I understand what you’re saying and actually that question is crucial. If you consider the idea of borders, it is inevitably connected to an urge to make the Union go to the dogs. Why was this Union even established? Because one wants it to fail. That’s how our minds work. The idea is not to stop when we’ve moved 30 kilometres down that path. That’s not how it goes. We need a continuous goal. And that goal is the United States of Europe, isn’t it?

And, well, I could have dreamed of this when I was younger. But in the beginning, I wasn’t a very big supporter of the common market, but that changed since then. Because it actually functions as a peace project too. It ties together that which should never be untied.

I’ve seen the fall of the Nazi regime, and I’ve seen France and Germany beat the hell out of each other. And if the axis that has been created can be kept as axis for peace, by which Kohl and Mitterrand stood hand-in-hand by the graves of soldiers – well, what more could you want? If one wants to be protected, that is.

But that’s not where we’re at. Not just yet. And the EU as a peace project, though young people won’t buy that today. It’s not enough. We could bring all the wars and occupations to the table that we wanted, but the young people cannot imagine what would make France and Germany fight. That’s a project which no longer sounds convincing. And if you remove that project from the EU I know, then you’re left with so much administration, and so little of the other stuff.

Well, the idea of the EU is based on paragraphs and articles in a constitution, but nothing is keeping it alive. The paragraphs are not seen as nutritious in their own right, they are not seen as vitamins. But they actually are if you arrange a parade with drums and banners and pretty horses.

Christensen: Yes, that would put it straight, wouldn’t it?

Barfoed: Yes, then you would get your vitamins, your muscles and your self-esteem: Yes, that’s me, and that’s who I am. But in relation to paragraph this and that, we can’t have people thinking oh, is this not just someone trying to make us believe something? Aren’t they just sitting there in Brussels with their newspeak trying to make me believe something? What’s in it for me?

Then you forget how much is in it for them already. Financial support systems and so on. But that’s not regarded as the result of a European fight. It’s not regarded as a perk that comes with the agreement we’ve signed.

Christensen: It’s taken for granted.

Barfoed: Yes, by rich people, right? By the rich – they have enough money.

Christensen: Yes, well, we’re already moving towards this: the question where I ask you to look into the future, as we’ve already talked about. But I want for you to focus in particular on how you perceived the future when you were younger. Were you an optimist or a pessimist when you were in your 20s? Did you think any of it might happen – the fall of the Berlin Wall and so forth could actually happen?

Barfoed: First, I just want to say that to me, the future wasn’t connected to anything political until the mid-1960s. Before then, the future to me was: a twosome, love, a woman. To experience nature and the universe.

I’ve never been religious in a confessional way. But more broadly speaking, I’ve had a religious inclination, which, however, has never taken the form of a confession.

But the future lied in – and this might sound silly – experiencing the world as a mystical, wonderful, meaningful whole. That’s part of being young, isn’t it? And to experience it with women, lovers, friends and so on.

But then of course something happens – and I find this crucial – the welfare state begins to manifest itself in Denmark. Viggo Kampmann becomes Prime Minister [Denmark’s social democratic Prime Minister, 1960-1962] and later on Krag [Denmark’s social democratic Prime Minister, 1962-1968] takes over. And they suggest ways of doing things which are so completely different from the norm at the time.

Before they were elected, politics was decided by the upper house and the lower house of Parliament. And they were all wearing wing collars and herringbone coats. And this kind of politics had suffered immensely during the occupation, so when the old politicians had returned, they smelled a bit ‘fishy’, you know, from making compromises with the Germans, and now the old world was just supposed to return.

Because then we were living during a time of peace and with great living standards. The word ‘liberation’ ruled our lives. It became a golden word. We were supposed to become different people after the liberation, but what were we liberated to do? We couldn’t see it.

Then it was all about how the old politicians could just brush off their coats and polish their shoes and spats and then they’d sit down, taking up all the space and continue what they were doing.

Actually, there was this kind of what-the-hell attitude towards everything. Why do you need politics? What should you do with it, anyway?

But to me, that changed. For starters, regarding the welfare state, it was Villy Sørensen who told me what to think about it and I did what he told me without him dictating anything and without him realizing that I was just following his lead (laughs).

But the welfare state was established, and a sort of socialism returned with it. The welfare state is, in the best possible way, a socialistic initiative – they were socialists! He really was, Kampmann. Now you can barely tell what they are, the Social Democrats, they’re in bed with Dansk Folkeparti. Back then, something like that would have been completely out of the question.

Anyway. There were never any binding contracts. For me, the decisive things came from the outside. It came as Eastern Europe, simply put. Europe, you can say. And that experience was tragically connected to the fact that the price for Eastern Europe’s victory over Hitler was to let itself be trampled under Stalin’s boot heel. It really was.

They were being punished twice. First by Hitler, then by Stalin. How about that!

Christensen: Yes, that made you take action?

Barfoed: Yes, it did. And maybe my residency in the United States also had something to do with it, as I experienced a world-dominating democracy first-hand. I won’t make myself sound like a political hero in any way, though of course, that’s your job now, isn’t it! (laugh)

Christensen: Yes, that’s up to me now. (laughs)

Barfoed: (laughs)

Christensen: Yes, that’s marvellous. We just need to talk about a few more subjects. Let me know if we should take a break first. We still need to touch on conflict and resistance. You could say it’s been very present in everything we’ve talked about already.

Yes, what do you see as the biggest threat to the EU – is it internal dynamics or is it something external? This is a continuation of what we’ve already talked about.

Barfoed: Yes, it’s difficult to separate those things. Which is always a clever thing to say. But there’s no doubt about the fact that right now there is a movement saying that the EU is not satisfying its significant requirements for continuing to exist, for social security, progress and so on.

Especially in Eastern Europe, but partly also in Western Europe – not in Denmark for the time being – there is this search, which could already be seen when Slovakia exited its co-sovereign status with the Czech Republic, and Milosevic made so many improvements with his Serbians that all of the Balkans became incredibly fragmented in terms of nationalism and religion.

Christianity was suddenly a hit in Croatia. I saw my old friends walking around with crosses around their necks and I asked them: Have you lost your mind? Religion has been a political weapon in liberation fights and today we’re close, I mean really close, to some resolutions, probably making it difficult to impose any sanctions on Orbán, because one doesn’t dare to give him any punishment. No one dares to. Everyone is being very careful, because where would we be if he was subject to all sorts of challenges? Where would we be? In other words, what would it start?

But there was something I wanted to return to. And they’re being very careful, because where would it leave him, if they were to exclude and punish him? Where would that leave us? It could go terribly wrong, and we might be headed in that direction already. But, Floris, there was something I wanted to return to.

Christensen: The conflict in it, perhaps. The role of EU and all that mess.

Barfoed: Yes. I think it could go terribly wrong, because of the issue of making Europe a future necessity for each individual state, for those who also see Brussels as a new Moscow, to put it harshly, and who really cannot imagine themselves as part of the EU-project. They are increasing in number, these states – and even the Czech Republic is a combination of populism, nationalism and state corruption. That’s a combination which is difficult to match.

And I can imagine that the EU in one way or another has to – instead of trying to oversell their ideals – relax – but I mean, how do you relax when you have to deal with Orbán? Ah, alright, what the hell. You cannot say that.

But I do think there is a critical mood prevailing with regard the entire EU-project, now that you ask me to glance 50 years ahead. One can imagine the end of the EU as we know it and a model involving less connections between the different parts as the alternative. With Brexit and all the other exits which could potentially follow, it’s difficult to imagine a true consummation of the project.

And I also find it to be very complicated. The entire European election. How many people could you pull aside and ask: What does the European Council do? Could you just explain that to me? They wouldn’t know what you were talking about.

And that’s not their fault. And it’s not only because there hasn’t been enough lectures held about this subject. It’s something else. It really is. You’re looking to achieve a fantasy. What does a company do, if what it’s trying to sell no longer makes sense? What does a company do if it wants to survive?

One can see some manifestations of this problem. For example, just the fact that one couldn’t deliver a persuasive model to solve the immigration issues. Just imagine if they had said to themselves that the most important thing for them in terms of sticking together is their ability to find an answer to this misère, this challenge.

I think that EU’s survival depends on its ability to show initiative when it’s necessary. And there is enough money. It can be costly, but there is enough money. And there should also be enough energy.

It might be easy for me to say, but I really do think that it is the convincing, grand – almost universal – joint decisions which can solve such things. They will bring an immediate and comprehensible authority to the table.

But yes, right away it was quotas, quotas, quotas. But it didn’t lead anywhere. Do you know what I mean?

Christensen: Yes, a grand, well-planned initiative, which can mobilise.

Barfoed: It is a successful, unbelievably expensive initiative with clear advantages, with not too many humanitarian costs. It’s perfectly okay to be ready to indicate that you’re also ready to pay a small cost with respect to humanitarianism. I think that might persuade some. We can do this. We really can.

Christensen: So that’s where you find hope for Europe over the next 50 years?

Barfoed: Yes, but when you think about the machinery in place, that you have to have all members on board, then I think it will be difficult. They all have to say yes. And it takes time.

Christensen: Let’s see! (laughs)

Barfoed: I really appreciate that you can understand my musings, that’s what we need! Especially from young people. How old are you?

Christensen: I’m 30. And perhaps we can finish now with a question about the future. Your hope for Europe’s future generations. Do you have any ideas or advice that you would like to pass on to my generation or to future European generations?

Barfoed: Okay, now you’re addressing my inner priest, and he doesn’t take up a lot of space, but let’s see. Well, I think I’ve always found that Danish youth or the young people in Denmark have been living on a different planet, sort of, then a lot of other young people in Europe, especially those in Eastern Europe.

Really, when you think of the butcher’s bench, which Eastern Europe has been to my generation, how sodded with blood the earth is in that area, you cannot put a shovel in Belarusian ground without touching a skeleton from a person who has been shot in the neck or hanged from a rope.

I so wish that everyone at an early age was made aware of the circumstances and brutality, that people around the world were subject to and developed the desire to learn more about the world – not just gastronomically. Because of course, it can not only be interesting to know how they make pizzas in Italy, but also to know how young people are destined to live, whether they are in Africa, Eastern Europe or India.

We all know how to press a button and make the Internet appear on our computer in no time. But how do you make yourself aware of different life circumstances around the world? You only do that by going there and actually touching it. And I think, in a way, I had a poor childhood and youth, which was determined by exactly this

imprisonment. We were very privileged, but all my contemporaries outside of Denmark, they were in shit up to their necks.

It’s actually so very banal. Get up and get out! I will never forget the fact that I have a grandchild who finally found the courage to leave, and she chose Paris – and that’s good, as long as it’s very far away – and a couple of days after she left she called her mother and asked her, how much salt to put in the boiling pasta water. (laughs)

This would never have happened when I was young, even though the telephone was invented by then. First of all, telephone calls were insanely expensive and reception was terrible. And it could easily take a while if you were calling from a phonebooth. Because you didn’t bring a phone to Paris, did you? Then you had to sit there and wait for your call to be returned. And now you call home to ask how much salt to put in the pasta!

But really, the fact that she goes to Paris deserves respect and you cannot ask for behaviours which belong to the past and have been surpassed by modern means of communication. You cannot do that. So therefore, I don’t know what to say to you other than what I already have.

And that really means: Don’t be afraid! Get the hell out there! (laughs) It’s something like that.

Christensen: Also, specifically in terms of Eastern Europe – in another interview you’ve said that it might be smart to re-establish connections to intellectuals from that time, such as those in places like Belarus, for example?

Barfoed: Yes, definitely. Completely. Poor things, they’re dealing with a lot of shit, aren’t they? Belarus has gone missing! It doesn’t exist on the map. But it will, and then Europe will be busy (laughs). But well, maybe I’m getting tired, but we can easily redo something or I can write you something.

Christensen: I think we are exactly where we should be. I just want to say thanks a million! This was really good and interesting.

Barfoed: Yes, well, it’s not very demanding and that’s because immediate contact with other people has always been crucial for me. It’s a thing that’s right around the corner, he or she might be waiting. It’s always a good idea to knock. Either you get told off, like I did by Biermann, or you get something else. I once met an old lady on a street in Prague in 1985, who asked me: ‘Excuse me, sir, would it be okay if I touched your coat?’

I was wearing an army coat, so she saw how fine clothes were still made in the West. She couldn’t stop touching it, and, thank God, we started talking. And she became a figure in one of my articles, because she could talk to me about the tailor, who had been sucked into a co-operative owned by the state.

It’s all there. That’s how I’ve worked. I’m not one of those people, who has a great complete analysis ready of Europe and of the tech-giants. My work has always involved meeting people.

Christensen: This has gone exactly as it should have. I’m very happy and satisfied.

Barfoed: But please do let me know if you need anything else.