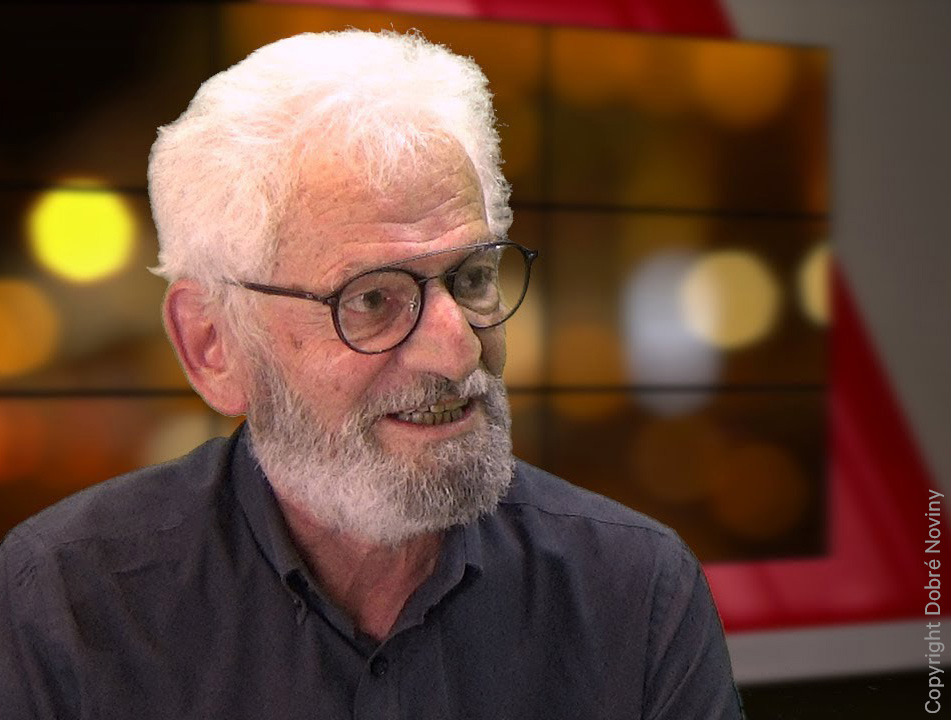

Egon Gál is a Slovak philosopher born in 1940 in Partizánska Ľupča, central Slovakia. In 1944 Gàl and his family were deported to Terezín. He survived and together with his mother and brother moved to Bratislava in 1948. Gal’s path to becoming a philosopher is highly unusual. Having originally studied chemistry and working in a chemistry lab, his interest in philosophy was initially triggered by an informal philophy reading group that he started with a group of friends. He got increasingly more engaged, and developed a keen interest in the cultural history of the sciences in particular. Following the shutdown of the Marxism-Leninism departments after the upheavals of 1989, new philosophy departments were emerging, and Gàl eventually became head of the department of philosophy at the Comenius University in Bratislava.

In this conversation with Tereza Reichelova, Egon Gál talks about his first time traveling to the West, challenges and constraints for intellectuals before 1989, and the changes in Slovak society in the 90s. Having experienced different regimes, Gàl is optimistic about the future of Europe – if we are able to create a common narrative for Europe that strengthens the European identity and solidarity.

Egon Gál was interviewed by Tereza Reichelova, who studied political science and philosopy in Prague, and works as an author and project manager for Civic Belarus.

Interview Highlights

About school

[in 1948] I started to go to a Catholic school, Notre Dame, where nuns used to teach […]. But the next year they disappeared, and comrade teachers took their place. I came in Year 3 and that year we prayed and then the next year we sang [communist] songs at the beginning of the lesson. But it’s interesting that we, children, didn’t take it very dramatically. You know children… The only thing was that when entering the classroom, we were supposed to say “Hail labour!” and we somehow didn’t feel like that, so we always waited for some other classmates to arrive and did it together.

About work

I’ll tell you how I was confronted with the issue of my identity. In 1989, when PAV (Public Against Violence) was established, I worked in a research centre for cables. And it was at the beginning of the year 1990, when the research centre didn’t have money and it had to dismiss some people. They dismissed twenty workers and one of them was a person whom I knew very well. I was helping him with his PhD, we were quite compatible, but he was very argumentative and the biggest conflicts he had were with his bosses. So, he was among the first people who were fired. I went to work one day, I think it was in February 1990, and there was a poster with an inscription “These Jews are responsible for my dismissal”. There were six or seven names but none of them was a Jew. So, I came to him and I say: “Colleague, none of these people is a Jew! I am a Jew but out of the people, whose names are written there, nobody is a Jew!” We quarrelled, this one’s brother-in-law is a Jew, and the other one’s too […]. Soon, I gave up and went away. The following day I went past the poster and the word ‘Jews’ was crossed out and replaced by the word ‘Zionists’. That was the first time I realised that this identity means something.

On the transition in the 90s

This beginning of the 1990s was a dream for us. We thought we had become a part of the West. But the West we imagined was different from the West we became a part of. […] There was identity politics on the one hand and on the other hand, huge inequalities, neoliberalism and loads of things, which we hadn’t seen before but mechanically copied from the West. When I was in America in 1995, Rorty told me that they were quite disappointed about these Eastern intellectuals because they were expecting to learn from us something about the world they didn’t know anything about, something we achieved. But they realised they’ll not learn anything from us and that we are copying them in every imaginable manner. We simply didn’t expect that. We got drunk on freedom. But the social life – inequalities, emergence of nationalism. What depressed me the most was that suddenly you could see homeless people in the streets, suddenly all those poor regions emerged around Slovakia. That is one thing. The other thing is nationalism. Ethnically defined parties were established, religiously defined parties were established, I was shocked. And I was worried.

About the European community

The question after the cause of enlarging this circle is a key question, I think. The first factor is religion. Religious narratives. Why are Enlightenment science, humanity, rationality, human rights, why are they unable to be so effective as religion? Because they didn’t create any narrative, they didn’t create any heroes with whom one could identify, they didn’t create symbols and they don’t elicit emotions. The core around which human morality is built, is emotions. And the biggest community that appeals to emotions, so far, is the nation. Every community bigger than that is a matter of rationality, not a matter of solidarity and values that are built on morality. The question is whether we will create a narrative for Europe with which we could be able to identify. I almost think we won’t, you know. I don’t know, I might be wrong. But if we don’t come up with it in next 50 years, rationality must prevail.

About the future

How will the world of the future look? If you look at the world of the past and the technologies that didn’t exist, considering Europe overall – regardless of one’s relation to or opinion on the past – the last 200 years in Europe is a success story. All measurable aspects and quantities are ameliorating, people live longer, they are healthier, more educated, there is less violence, we are richer, more literate and despite all this we live with a feeling of permanent crisis, that’s peculiar. There is an endeavour to understand, that is what the feeling of permanent crisis is all about.